During beers with friends, we started telling travel stories. As one story topped another, I described the time I attended a voodoo ceremony in Haiti. That story topped them all. No one goes to Haiti anymore because of its political instability. Likewise, no outsiders go to voodoo ceremonies there. Not that many went when I visited. Haiti was never high on tourist destination lists — although the country it shares the island of Hispaniola with, the Dominican Republic, is very popular. When I visited, the country was in a deep funk. Since then, it’s gotten worse.

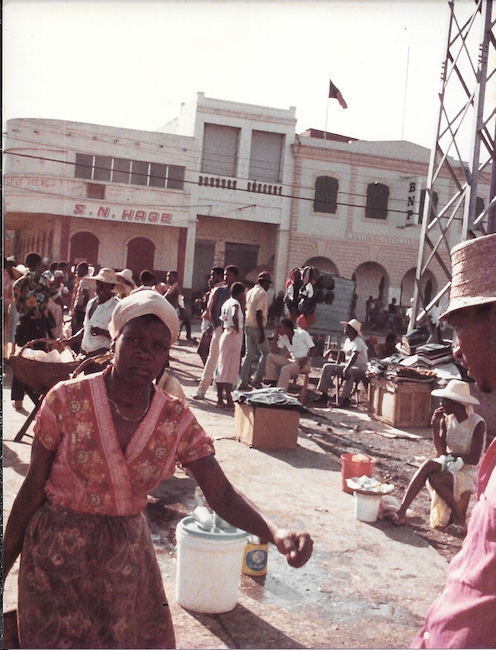

Arrival in Port-au-Prince

I arrived in Port-au-Prince, capital of Haiti, on an American Airlines flight from New York in September 1984. Although long ago, the memories of my visit are as vivid as if they happened yesterday. Haiti can imprint its mark on a mind like that. When I departed the plane and stepped onto the tarmac, I saw Haitians crowded on the outside terrace of the terminal’s second floor. The terminal, a decrepit, boxy white building, was the main route out of the country. The Haitians gathered there looked sullenly at flights that would bring family members back or take them away.

An offer I should have refused

After clearing immigration and customs, I grabbed a taxi to my hotel in Petion-Ville, a suburb in the hills east of Port-au-Prince. It’s cooler, calmer, and above the din of the capital. I didn’t speak Creole or much French, but the taxi driver spoke broken English. He offered to be my tour guide of Haiti, which I turned down since I figured I could arrange trips through the hotel. But before he reached the hotel, he made an offer I didn’t refuse. Even if I should have.

“Would you like to see a voodoo ceremony? One is happening tonight in Port-au-Prince.”

“Sounds cool. What time?”

“I will pick you up at midnight.” Broken though his English was, it was precise.

I thought: wait a sec, a midnight taxi ride to a voodoo ceremony in Port-au-Prince? That’s crazy. This is Haiti, after all. Who knows where I was really going and if I would come back.

“See you then,” I said.

Midnight ride to a voodoo ceremony

At midnight, I walked down the hotel’s stairway and crossed the barren lobby. As I was about to exit outside, the receptionist called out to me, “Monsieur, where are you going?”

I turned and smiled. “To a voodoo ceremony.”

“Wait,” he said in alarm.

At that point, the taxi roared to the front of the hotel, the passenger door flying open. No sooner did I climb inside than the taxi roared off.

Past slums and palace in Port-au-Prince

After half an hour, after a descent from the lush hills of Petion-Ville with its view of the shimmering moonlit Caribbean, the taxi was crawling through the patchwork dirt roads of Cite Soleil. While the words mean Sun City in English, it was Port-au-Prince’s most notorious slum.

At this point, I thought, “This might not be the smartest thing I’ve ever done.”

Soon, we drove by the colossal Presidential Palace, where Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier, son of the vicious dictator Papa Doc Duvalier, ruled. A three-domed palace, it was surrounded by high iron gates, guard posts, and roving pairs of his notorious secret police, the Tonton Macoutes, who during the day were as infamous for their large, dark sunglasses as they were for their senseless and sudden brutality. Just two years later, in 1986, “Baby Doc” was overthrown by the Haitian people and sent into exile in Paris.

Past the palace, now about 45 minutes into the drive, I asked the taxi driver, “Are we almost there?”

He turned to me, his smile bright in a way that dimmed my mood: “Soon.”

In a neighborhood with lush foliage, we pulled into a long driveway with a darkened, colonial-looking home at the end of it. It looked like it belonged in a Graham Greene novel, which wouldn’t surprise me since he set his novel The Comedians in Haiti.

“We here,” he said.

Voodoo hounfor

I stepped tentatively out of the car. A woman wearing a white dress greeted me with a solemn expression and led me around the side of the house to the back. We stepped into an open-air area, a hounfor, a voodoo place of worship. There was just me and a couple who looked Latin American. I acknowledged them and they me, but we didn’t speak, nor did we stand near each other. We shared one thing in common, though: an uncomfortable feeling. By now, it was past 1 am, and the sticky heat of Port-au-Prince was making my skin sweat and my flesh crawl.

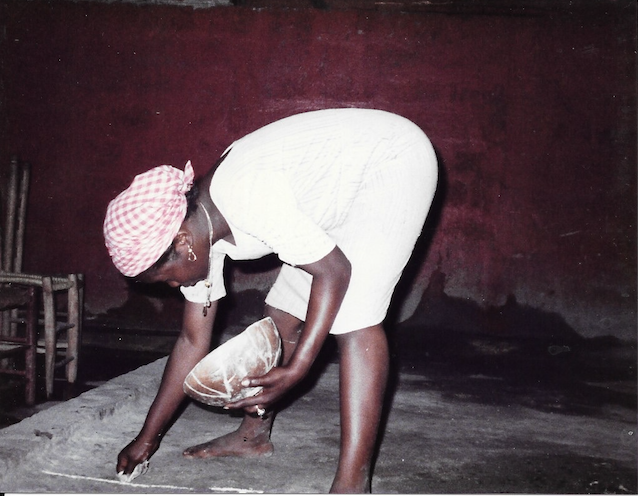

The Latin American couple and I sat down and continued to keep our distance from each other. We sat on the edge of a concrete circle and watched while the woman in white with a checkered bandana bent down to finish chalk markings on the ground and place lit candles near them. What the chalk markings meant, I had no idea. But I wish I did. Another woman, also dressed in white with a red bandana, confronted another woman who wore a red dress covered in white tropical flowers. They spoke to each other in a challenging way around a simple white step mound with a wooden stake rising from the center of it. A tall, gaunt man in a loose pink shirt and trousers banged the wooden stake with a rhythm that was off and not melodious. I wondered: was it ritual or theatre? Or is all ritual really a kind of theatre?

The voodoo ritual begins

A few Haitians emerged from the shadows at the edge of the hounfor. There was a subdued and suppressed feeling in the air. But I was there now. I wanted to see how this played out. The woman with the red bandana was the mambo – a voodoo priestess. She started to chant. But her tone was more staccato, guttural, than melodic. I’ve attended an Apache Crown dance in a chaparral landscape and a Hopi Katchina dance in a kiva on an Arizona mesa — the chanting at those dances had a certain melodic, somewhat pleasing rhythm. This chanting didn’t.

Every now and then, I was able to sneak off a shot, but I received a sharp look from the tall man in pink when I did. The photos I took are surreptitious.

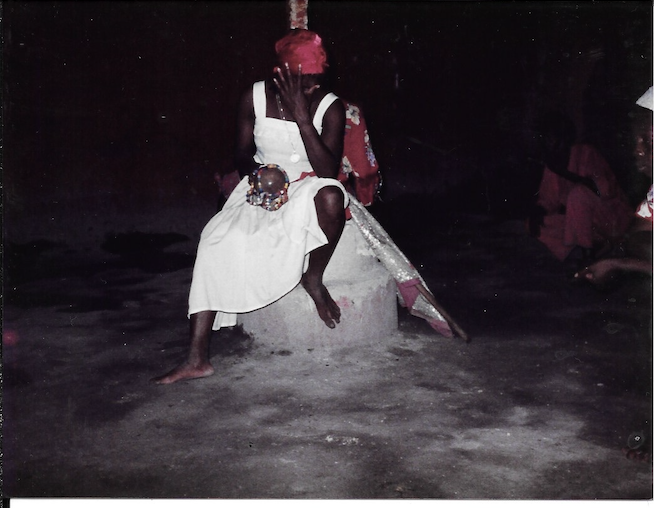

The mambo with the red bandana sat on the mound and held her face in a kind of contemplation with one hand and a hollowed-out gourd threaded with beads in the other. Then she started to chant more insistently as she moved menacingly around the concrete circle. The first time she circled, she howled in my face. The second time she circled, she spat liquid from the gourd in my face. I wasn’t sure what the liquid was. It didn’t smell and wasn’t sticky. But it didn’t seem like water either. To this day, I wonder: did she do that because it was part of the ceremony or because she could? I wiped my face with my sleeve but otherwise didn’t react.

The tempo of her movements increased as the other woman in the flowered dress started to writhe on the ground in a trance, first faced upwards, then on her belly as she put her face and body onto the chalk drawings. Her movements were spasmodic. The mambo set aside the gourd to give her a live, agitated chicken, its feathers ruffled. The woman on the ground clutched the chicken and, in an action that was sudden and savage, ripped its head off with her teeth, blood spurting across the concrete. A shriek split the air, followed by the thock,thock, thock sound of the wooden post being hit with a stick by the tall gaunt man. I was startled, but while my head moved backwards, my feet were planted, and I stayed where I was and didn’t step away from the concrete circle. Nor did the Latin American couple. The woman spat the chicken’s head onto the ground and its blood into the gourd. The ceremony had reached its crescendo. The woman collapsed near the mound. The mambo sat on the mound and stared down at her, almost as if she were a kind of victim. The thought that she might become a zombie — Haitian voodoo is known for turning people into them — crossed my mind. But it just as quickly left it too. I found out later that the sacrifice of the chicken was to appease the lwa, a primary voodoo spirit.

Back to the hotel for a restless rest

Drained, I was led away from the hounfor, along the side of the house to the front. The taxi was waiting for me and took me back to the hotel. The driver didn’t say anything on the drive back as we passed the Presidential Palace and drove through the Cite Soleil, pre-dawn life starting to emerge on its dirt alleys and broken asphalt lanes, from its zinc-roofed ramshackle dwellings.

At the hotel, I paid the driver and walked past the relieved receptionist to my room. It was around 4 am. I had spent most of the post-midnight night at the ceremony.

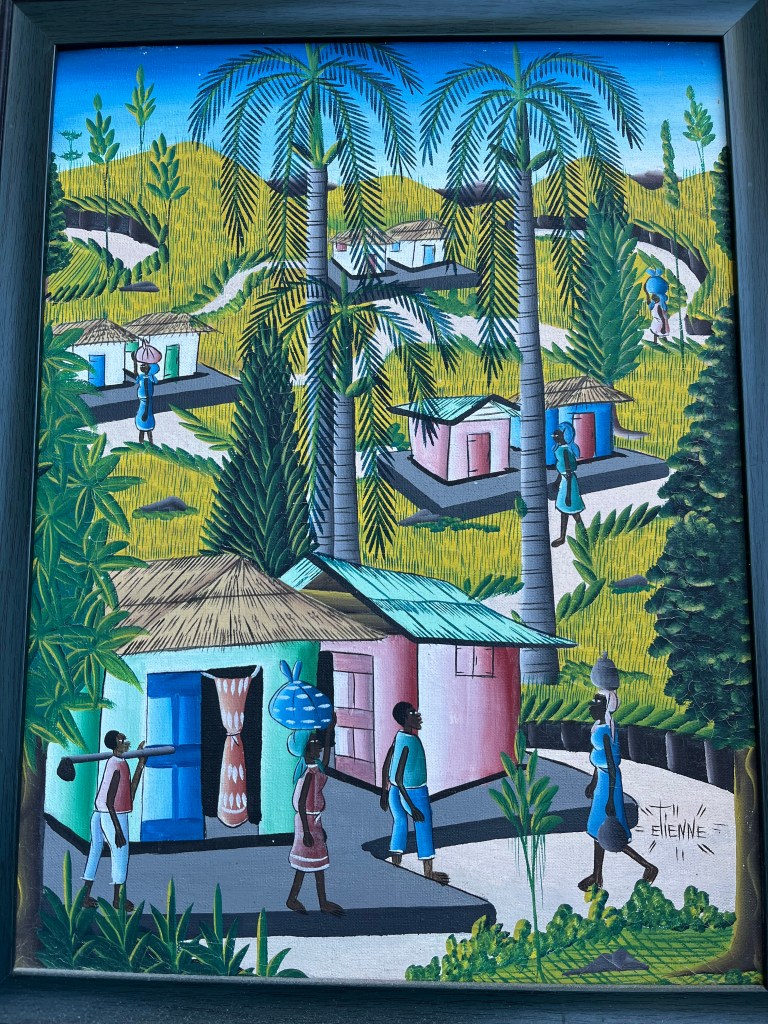

A visit to sun-dappled Jacmel

As I lay on my bed in my hotel room, the images from the ceremony raced back into my head, hindering my ability to sleep. After dawn, I took a bus to Jacmel with its 19th-century gingerbread mansions supported by narrow, rusting iron pillars. Wraparound balconies provided the residents of these expansive homes with great vantage points to see what was happening in the town. Only, no one was on the balconies the day I visited. You could say that Jacmel’s architecture looked like New Orleans’. But that would be false: it was New Orleans architecture that was influenced by Jacmel’s in the late 19th century, when Jacmel was a wealthy coffee port. In the scalding sunlight of one of Haiti’s most peaceful towns, with its deserted art galleries, a tranquil waterfront, and sleepy streets, Jacmel was 50 miles by road from Port-au-Prince yet a million miles from the turbulent voodoo ceremony of the previous night. I bought a painting here, and it hangs above my bed, above my head, so that every night Haiti is influencing my dreams.

Leave a comment