The graffiti on the outside wall has the look of urban scrawl everywhere: “We protest against the dictatorship of the club president!” The president of the Bengal Club in Calcutta, founded in 1828, was just trying to enforce some club rules, and he seems to have run headfirst into a wider force. Calcutta’s genteel clubs are having to reckon with the culture of protest that has always existed outside their forbidding white-washed walls.

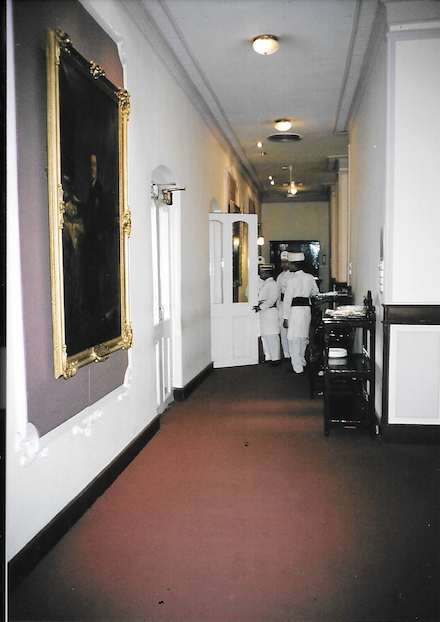

Inside the Bengal’s stately building, members speak in hushed tones. A steel-gated elevator clatters you to the second floor, where the same dining tradition has been maintained for over 150 years. The waiters, wearing white tunics with brass buttons and wide black sashes for belts, look like they stepped out of a Rudyard Kipling book. The paintings on the walls are of old British sahibs – the respectful Indian term for Europeans. Those men are now probably buried in the crow-filled, weed-covered South Park Street Cemetery a few blocks away.

The Bengal’s graffiti hardly fits with the gentlemanly, antiquated spirit of the place. But then again, Calcutta is notorious for its culture of protest. People in this city have always taken to the streets, whether to be among the first to fight colonialism – or later, whatever happened to the national government of the day. It was this spirit of rebellion that led the British to move their capital to New Delhi in 1912.

Clubs are popular in Calcutta, now officially known at Kolkata. No, not dance clubs where girls in short skirts and guys in tight shirts hang out. Calcutta’s night life is pretty tame in that respect. These clubs were started by the British to deal with homesickness and the dull, distant colonial lifestyle. But when they left, the tradition stayed – carried on by the society’s elite: barristers, lawyers, doctors, engineers, businessmen, even the occasional maharaja, or local prince.

Another landmark, the Saturday Club, was founded in 1875 by the Calcutta Light Horse Regiment. The current club premises, built in 1900, are entered by passing beneath a series of flags and a small balcony where a dignitary might wave to well-wishers. On the other side of the grand ballroom, covered in a parquet floor with huge fans hanging immobile from the ceiling, you can reach the Light Horse Bar. When the regiment was disbanded after India gained its independence, its trophies moved there.

Then there’s the Royal Calcutta Golf Club, also known as the “Royal.” Founded in 1829, it’s the oldest golf club outside of the British Isles. It was King George V who gave the club its “royal” title at the Delhi Durbar in 1911. The building that houses the club now was opened in 1914. It looks like a sprawling lord’s manor with a red-titled roof and red trim around the windows, doors and grand entranceway. The lawns are vast and manicured. Inside, it has the austere atmosphere of a British public school. Long mahogany boards list the names of gold-medal winners in gold lettering all the way back to the 1870s. Black and white photos of stiff-looking club presidents line the stairway to the second floor. Beneath the striped awning out back you can watch golf, or just sit and drink tea.

Nearby is the Tollygunge Club, founded in 1895, which is spread over 100 acres that surround a more than century-old clubhouse. You can find golf, tennis, squash, swimming or even horseback riding here – just like those denizens of the Raj did so many years ago. In a city mired by poverty, this is where the gold leaf thin top tier of society spent their leisure time.

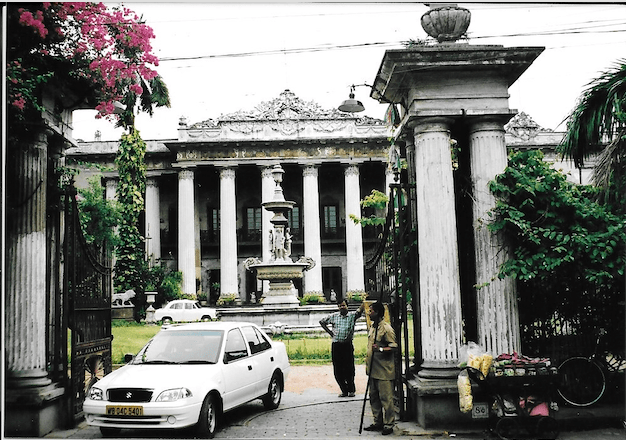

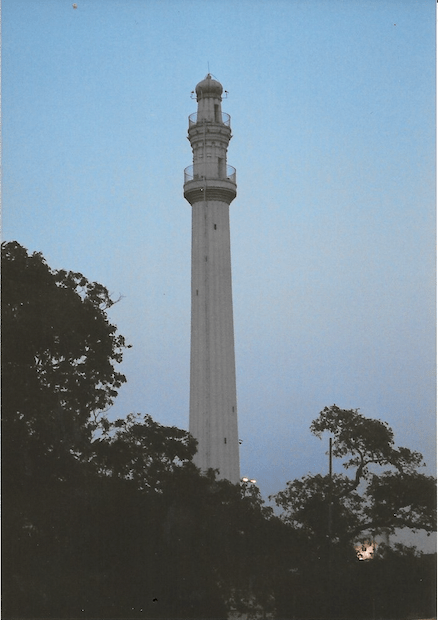

It might seem strange that Calcutta should play host to so many antiquated British institutions. Yet up until 1912, Calcutta was the second-largest city in the British Empire. The Victoria Monument here was built by Lord Curzon between 1906 and 1921 in memory of his empress and was meant to be larger and more impressive than the Taj Mahal. The former Dalhousie Square, now known as BBD Bagh, was the bastion of British bureaucracy, with impressive colonial-era edifices surrounding it. The massive 200-year-old British Government House is now known as the Raj Bhavan and is the seat of the West Bengal government. Nearby is the Doric-style Town Hall and the High Court, copied from the Staadhaus at Ypres, Belgium and opened for justice in 1872.

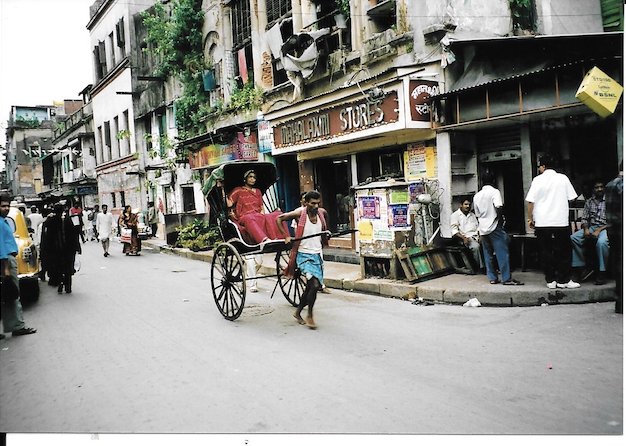

Because it has seen so much war, poverty and turmoil, Calcutta has not torn down its past. It has simply been too poor to build many new buildings. The result is the largest “museum” of British colonial architecture in the world. Think of it as a tropical 19th-century London. Add to that the antique-looking Ambassador cars with styling that hasn’t changed since the 1950s and the human rickshaw pullers, and you could be worlds away from the rapid development of Indian cities like Mumbai and Bangalore.

The graffiti on the wall does suggest that tradition could rapidly slip away from the clubs that Calcutta has nourished since the days of the British Raj. Nevertheless, these traditions are still more intact here than in most other parts of the world.

Published in The Asian Wall Street Journal, August 12-14, 2005

Leave a comment