As the free world hunkers down for the first global war of the 21st century it’s worth taking a glimpse at a place where the last global war ended: at Tinian Island, where the planes that dropped the atom bombs on Japan took off. My family recently took a trip to Tinian, a Manhattan-shaped island in the Mariana Islands where the Manhattan project neared its end. Colonel Paul Tibbets, piloting the B-29 Superfortress named Enola Gay, took off from here to drop the bomb, “Little Boy,” on Hiroshima. Three days later, Major Charles Sweeney, also took off from here in the airplane named Bockscar to drop the bomb on Nagasaki.

At the end of World War II Tinian was the busiest airfield on earth, with six gigantic runways. Nineteen-thousand combat missions flew from here. Now it’s a quiet place with some unusual attractions. With a population of less than 3,000 people in an area of 39 square miles, it lies next to Saipan in the Mariana Islands and is politically part of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, a U.S. territory.

When we got off the boat from Saipan, my family’s first stop was the casino that today is the island’s largest business. Tinian Dynasty Hotel and Casino is a flash place — a Macau-style casino occupying a piece of South Seas paradise. But unlike other hotels in the tropics, it doesn’t leverage its location. No al-fresco dining to pull you away from the gaming tables. The windows in the rooms don’t open to let in the warm breezes. After all, you might be tempted to enjoy the tropical weather outside — leaving the pleasures of the slot machines behind.

We started our touring by driving to the Suicide Cliffs on the south side of the island. As American troops were invading the island at the end of July 1944, Japanese civilians chose suicide rather than surrender. They jumped to their deaths from here. Their fanatical behavior has an eery parallel with the terrorists of today. The site is spectacular and empty with vertical cliffs dropping to crashing waves and a sea of startling blue. We were the only visitors, deepening the natural solitude of the area and making it feel as if we really were in a sacred place.

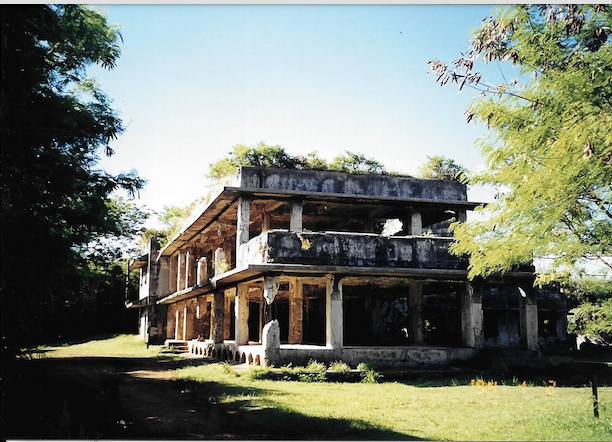

From there we drove clear across the island. Because Tinian is shaped like Manhattan the military named the island’s roads after streets in New York. Broadway is a long straight avenue, but unlike its famous namesake there is no traffic at all, no pedestrians, and only a few gutted buildings from World War II days. Weeds sprouted from the asphalt. Jungle is starting to creep in at the edges.

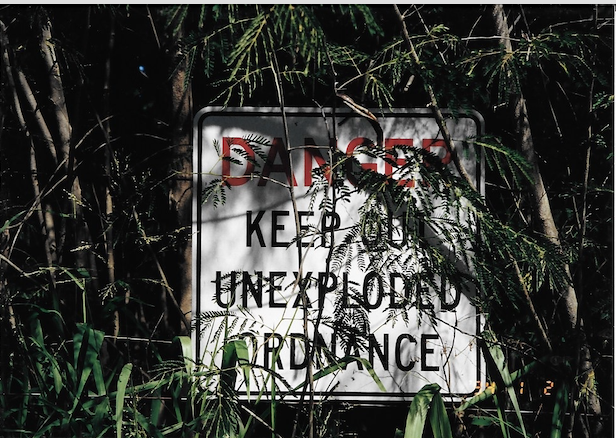

At a roundabout there was a ruined Japanese shrine. We drove around it to a truly forbidding part of the island. The road narrowed and every couple of yards there were signs on jungle-covered barbed-wire fences that warned of explosive ordinance. After a couple of miles there was a dirt turnoff to the left where we stopped next to a large grave-size plot with a few flowers on it and a headless palm-tree in front of it. A wooden sign read, “Atomic Bomb Pit No. 1.” The plaque described how the bomb dropped on Hiroshima was winched into the belly of the Enola Gay at this spot.

About 50 feet away was another signpost: “Atomic Bomb Pit No. 2.” Another atom bomb, “Fat Man,” was winched into the belly of Bock’s Car here prior to its journey to Nagasaki.

I’ve visited the Los Alamos laboratories in New Mexico, where the U.S. atomic bomb project feverishly was pursued, and its museum. I’ve also visited the museums at Hiroshima and Nagasaki and saw the horrors that befell the victims of the bombs. But this site at Tinian affected me the most: the silence; the complete absence of tourists or any other people; the sense of decay as if we were standing in a post-nuclear war world, one decimated by atomic weapons.

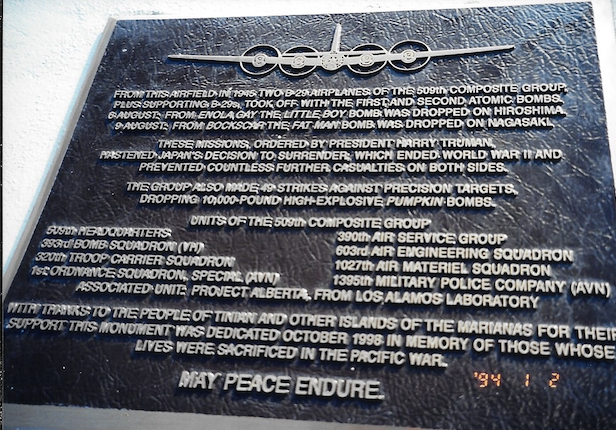

Further on we discovered the runways, monumental ribbons of concrete, now silent and slowly being reclaimed by the lush vegetation of the surrounding jungle. Near some Japanese bunkers on the side of one runway were plaques honoring the U.S. military units that served here. Then we found ourselves driving down the very straight 8th Avenue towards the hotel. We passed the sign for the 509th Bomber Group and its slogan bragging that it was the first to use atomic weapons. This was Col. Tibbets’s unit.

With some relief we reached the town again. We visited the ruins of a previous civilization: a collection of huge latte stones — like a South Pacific Stonehenge — that were the foundations of a home belonging to a legendary Chamorro chieftain, Taga the Great. Within moments we were back at the familiar surroundings of the casino. Other than the gambling and eating the only other entertainment at the hotel was a troupe of Russian dancers. But as I sat down to watch them gamely doing their routine I realized that I was the only one in the audience. It was an empty house.

Published in The Wall Street Journal, March 1, 2002

Leave a comment