In 1542, sailors on a Portuguese ship heading to Japan spotted Taiwan and named it Ilha Formosa, beautiful island. While driving along the coastal road from Taipei to the Ju Ming Museum it’s easy to understand how the sailors arrived at that name. The coastline, studded with rock formations, is at once dramatic and forbidding. It may have also served as inspiration for Ju Ming, Taiwan’s greatest living sculptor.

His museum, opened in 1999, was designed by him to showcase his vision in bronze, stone, clay and wood. While the focus on primarily one artist’s work is unique in Asia, in a nod to inclusiveness great artists from the both East and West are also exhibited. Taiwanese painters such as Chang Wan-chuan, Lee Cher-fan, Liao Chi-chun as well as Western artists such as Henry Moore, Andy Warhol, Joan Miro, Picasso, Bernard Buffet and Robert Rauschenberg can be seen there. The closest to a Western equivalent to it would be the Rodin Museum in Paris or the Picasso Museum in Barcelona – but minus the ego.

Born in 1938, Ju Ming began sculpting as an apprentice at the age of 15. For the next two decades he modestly viewed himself as just a talented craftsman and sought teachers such as the sculptor Yang Ying-feng to mould and shape his skill into true artistry.

In 1976, Ju Ming’s work, including his iconic Taichi Series, was featured at Taiwan’s National Museum of History. His Living World Series furthered his reputation internationally. In 1994 his work was featured at the Hakone Open-Air Museum in Japan, the first exhibition by a Chinese artist there.

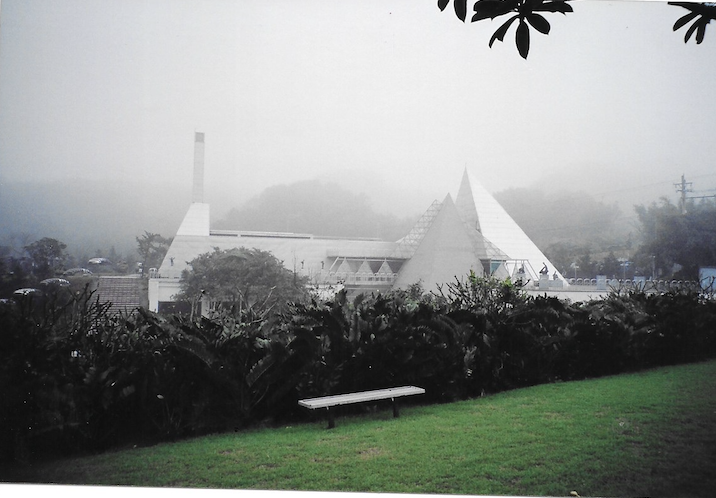

I entered the 11-hectare museum through a white angular building, descending some stairs before walking down a long, white hallway. I had the impression that the architect’s vision was that the hallway was like a birth canal and the outdoor exhibition just beyond the glass doors a new way to see the world.

I visited on a foggy weekday. Mist rolled over the works, at once obscuring and revealing them. Lack of sunlight dulled the color of the grass and the grey milkwood trees, but gave the works more gravitas as the Tai Chi figures were pushing at each other and the intrusive sky. The ever changing motion from the ground cover clouds helped to convey the stillness and movement of the figures, the uncanny sense that they were observers as well as the observed, like actors in a tableaux. While the figures were abstract or semi-abstract, the strength of their inner spirit was apparent. I was dwarfed by the size of the largest of the pieces, which at 15.2 meters wide by 6.2 meters high was the size of a small house.

There was a series of pieces on the Taiwan military. A platoon of life-size sculptures of soldiers was marching, exhausted, on a path. In another piece, soldiers stood at attention while an officer addressed them. There was an eight-story high bare metal frame of a naval ship, its mast lost in the fog of that day, while Ju Ming’s sculptured sailors were ready to be reviewed. His parachutists descended towards a landing zone beneath a bridge that connected the two sides of the museum grounds. Pilots stood impassive beside a mock-up of a fighter jet. His military were less enshrined heroes than people worn down by duty and obligation.

Whether it’s the Tai Chi masters or the Taiwan military, Ju Ming’s inspiration comes from the land of his birth. His angular Tai Chi masters look as if they emerged from the rocky shores the Portuguese sailors saw centuries before.

His stature, and statues, are helping Taiwan to carve a separate cultural identity, at once a part of and yet distinct from China. On both sides of the Taiwan Strait he is viewed as a great Chinese artist. A visit to his museum will show you why.

Published in South China Morning Post, April 18, 2007

Leave a comment