Nearly eight centuries after his death, Genghis Khan still rules the hearts of Mongolians, and his popularity is growing. Since the Russians were pushed out in 1990, a homegrown brand of Mongolian nationalism has started to reveal itself, with Genghis Khan at its center. His face is on the national currency notes, the togrog. A giant image of him has been carved into a mountain just outside Ulan Bator, visible from the city center. There are even calls within Mongolia to relocate the capital from Ulan Bator to Karakoram, the capital of Genghis Khan’s empire, on the 800th anniversary of its founding, which will fall around 2020.

These reminders of Mongolia’s glory days would not have been visible 20 years ago. When Russia ruled Mongolia from behind the scenes between 1921 and 1990, imagery of Genghis Khan was banned because he was such a strong symbol of Mongolian national pride. Mongolia’s domineering neighbors like to downplay the historical significance of this warrior leader, whose power was won at their expense. His empire became the largest in history, stretching from China to Russia to India to the Balkans.

It didn’t last. Mongolia was eventually invaded by its neighbors, becoming a fiefdom of China from 1732 to 1911, and then a puppet regime controlled by Russia for most of the 20th century. When protests toppled the pro-Soviet rulers in 1990, democracy took hold — and so did the public memory of Genghis Khan. At Sukhbaatar Square in Ulan Bator, a massive memorial to him is near completion. People line up to have their photos taken in front of it. An energy drink, a vodka and a beer are named after him, not to mention restaurants and tourist agencies. Mongolian legislators even debated a law to license his image last year, which would have allowed the government to charge royalties for use of the warrior’s name and control the ways in which his image could be used.

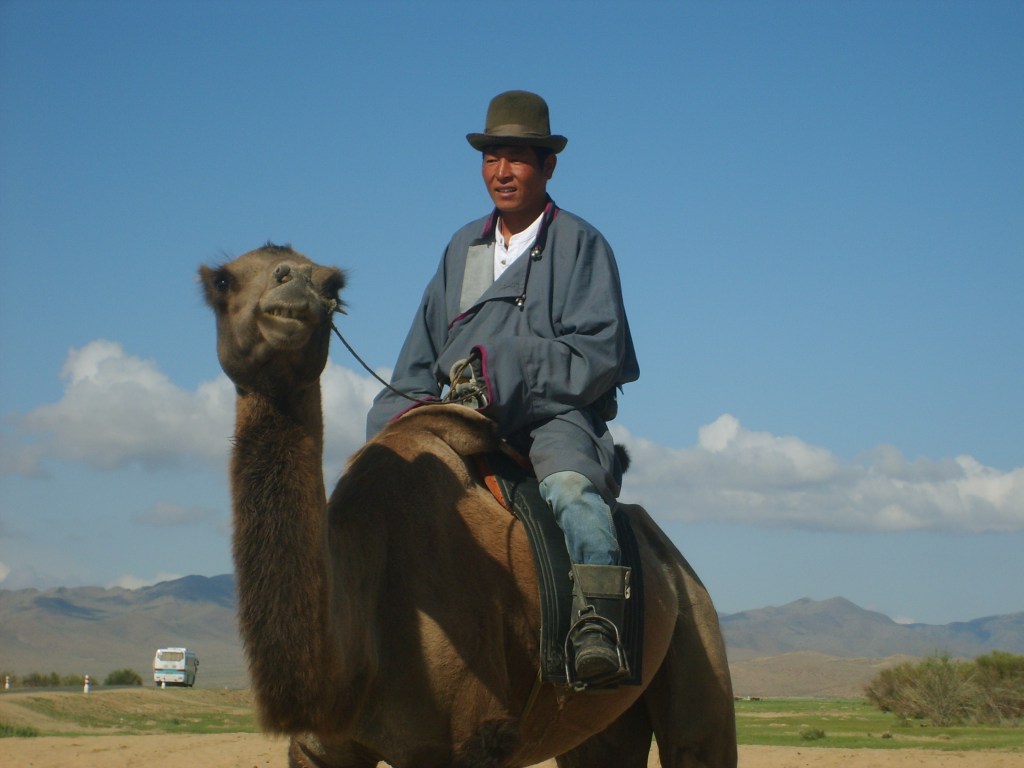

My guide when I was recently in Mongolia, a college student named Bolor, spoke of him in hushed tones, as if he were still living and very much in charge. Genghis Khan’s cultural legacy is also all around. The annual Nadam festival features the sports famous in Genghis Khan’s time: horseback riding, archery and wrestling. The fermented mare’s milk sold by children at roadsides and served by nomads to visiting guests was the fuel that powered his army on their conquests.

Genghis Khan may be best known as a warrior, but his legacy of governance is still relevant, too. He introduced a written Mongolian script still in use today and the rule of law, the Yasaq. He practiced a sort of religious tolerance that is progressive even for today: Citizens of the Mongol empire had no religious restrictions and could pray as they pleased – as long as they were loyal to the Mongol rulers. He unified warring Mongolian tribes into one nation and he and his sons conquered more territory in 25 years than the Romans did in 400 years. Mongolia is not the only nation in his debt — modern-day Russia and China were also first united under the reign of Genghis and his descendants.

In one respect it’s odd that a young democracy should so admire a ruler with such a fierce, autocratic reputation. Yet, the Mongol empire’s success was grounded on the principle of meritocracy. Ethnicity and race mattered less than ability. The Mongolians see Genghis Khan as the embodiment of that principle. That one man could so rapidly create so large an empire from such a remote outpost provides inspiration to his countrymen even today.

Published in The Wall Street Journal, November 2, 2007

Leave a comment