At the archaeological park Cihuatan in northwest El Salvador, the park’s sole guide told me that I was the only tourist that day and the only visitor, now that a school group had just left. At over 60 hectares in size, it’s the largest archaeological site in El Salvador. The guide walked me around a site that featured the country’s ancient and recent history. Dating from 950-1200, Cihuatan was a large Mesoamerican city built following the mysterious collapse of the Maya civilisation.

A perfectly preserved ball court was missing only the players that once animated it. In the quiet of the park, punctuated by the chirping of birds, I imagined teams of four moving a heavy rubber ball to a hoop to score, using only their hips, elbows, and knees to pass the ball. The winners of the game were sacrificed. If I played the game, I would happily be a gracious loser.

Next to a large pyramid is a huge Ceiba tree, known among the Mayas as the Tree of Life since they believed four Ceibas hold up the corners of the universe. The tree is pockmarked by bullet holes from army helicopters that fired at FMLN guerillas who took shelter behind it during El Salvador’s 1979-1992 Civil War. By protecting the lives of those guerillas, the tree lived up to its name.

At nearby Joya de Ceren, a UNESCO World Heritage site known as the Pompeii of the Americas, I walk through the ruins of a Maya settlement that was buried under six meters of ash when the Laguna Caldera volcano blew in 567 AD. Unlike Pompeii, no human remains were found — but there is a footprint preserved on ash, indicating that people hot-footed out of there to survive. Just a handful of tourists here.

From turbulent history to tranquil present

El Salvador’s turbulent history extends from the Maya era through the colonial era to the recent Civil War and the emergence of the violent MS-13 gang. The gang, which originated in Los Angeles to protect Salvadoran immigrants, metastasized into an international criminal organization that terrorized its home country. The murder rate peaked at 103 per one hundred thousand in 2015 and has dropped dramatically, especially under the strong leadership of current president, Nayib Bukele, to 2.4 per hundred thousand in 2023. Now El Salvador is more than two times as safe as the US with its murder rate in 2023 of 5.5 per hundred thousand.

Cobble-stoned colonial cities

The northern town of Suchitoto delights with evocative colonial architecture from its time as the heart of the indigo trade. Although it was the center of fighting during Civil War’s early day, the scars have been covered up. The Parque Central fronts the charming Iglesia Santa Lucia. Cafes abound and a fifteen-minute downhill walk on cobblestoned streets takes me to the shores of Lago de Suchitlan. Boats traverse the 135 square kilometer lake to take tourists to islands and falls.

Santa Ana is a grander colonial city with the imposing neo-gothic Catedral de Santa Ana, which opened in 1913, anchoring its center. Fueled by the lucrative coffee trade, growers built the lavish Teatro de Santa Ana, also on Parque Libertad, in 1910.

Small country, big landscapes

El Salvador’s vivid landscapes punctuate my trip. Lingering over a morning coffee I study the reflection of clouds in Lago de Coatepeque’s blue waters as it is framed by the Cerro Verde, Izalco, and Santa Ana volcanoes.

At the 1,893-meter-high El Boqueron volcano, there is another cone within its crater. On the Sunday morning that I visited Salvadorans enjoyed the park for its coolness and the views of the vast center of this volcano, which towers above San Salvador city.

At nearby Puerto del Diablo, two gargantuan rock outcroppings jut over sheer cliffs. There is a legend as to how it got its name, the Devil’s Door. The devil himself was courting Maria de la Paz, daughter of the wealthy Renderos family, until the family decided to hunt him down. When the devil was cornered by his would-be captors he broke through the middle of the rocky outcrop to escape, creating the opening that makes it look like a colossal doorway.

During the Civil War, the area lived down to its name. The army executed guerrillas and their supporters here and threw their bodies into the ravine below. A dozen hawks circled relentlessly the day I visited.

Hawaiians travel here to surf

El Tunco on the coast is known as Surf City. While strolling down the narrow lanes leading to the ocean I hear in addition to Spanish voices American and Australian ones. Nearly everyone, except for me, seems to be carrying a board either on the way to or from the beach. El Salvador has some of the best surfing in Central America and the world. During my recent visit to the Upcountry Farmers Market in Maui, a stall owner there spoke to a friend about a surfing trip she was planning to El Salvador. When Hawaiians want to travel to El Salvador for their waves you know they’re good.

A newly completed highway connects the beaches with San Salvador in about an hour — commuting distance. Greater San Salvador is becoming closely linked to its beach towns the way Los Angeles is to its seaside cities.

From notorious to noteworthy

San Salvador has a reputation for political and gang-related violence. The Oliver Stone movie, Salvador, depicting the journalist Richard Boyle’s experience during the Salvadoran Civil War, is engrained in many people’s minds as to what El Salvador is like even today. It isn’t. Not even close.

Today the city is a sparkling counterpoint to Stone’s out-of-date vision. Probably the best before and after juxtaposition is the Monumento a la Revolucion at the back of the Museo de Arte de El Salvador. The imposing monument, 25 meters high by 16 meters wide, is a mosaic depicting a man with arms upraised as if throwing off shackles. It was built to celebrate the popular uprising that overthrew the rule of the dictator General Salvador Castaneda Castro. The jewel-like museum features the country’s most famous artists, including the world-famous Fernando Llort. Next to the museum is the Teatro Presidente, an elegantly designed performance space.

An unflinching look at the past

To get a sense of San Salvador’s journey I visited sites that marked its Civil War period. The Monumento a la Memoria y Verdad is an 85-meter black granite wall with the names of the over 25,000 people who died or disappeared before and during the Civil War. Haunting sculptures capture the spirit of reconciliation. One shows two hands holding two sides of a split heart with a man and a woman hugging at the top.

One of the most notorious episodes of the Civil War was the murder of six Jesuit priests at the School of Theology on the campus of Universidad Centroamericana. It is now the Centro Monsenor Romero, with a small graphic museum that depicts Oscar Romero’s life and death, the murder of the priests, and the 1980 murder of three nuns and a laywoman, which was depicted in the movie Salvador. The military killed the priests along with their maid and her daughter because of their outspoken advocacy for the poor. A rose garden was planted on the site where four of the priests’ bodies were found. I found the garden peaceful as it was graced by flowers in bloom and eery.

The most famous victim of the Civil War was Archbishop Oscar Romero who was assassinated at the chapel of the Hospital Divina Providencia, also known as El Hospalito. On the day I visited a staff member showed me the chapel and Romero’s simple home across the driveway. The Toyota Corona that he drove was on display. His bedroom was simple, with a narrow single bed and the typewriter he used. In an adjacent room, the blood-stained robes he died wearing were displayed. It stunned me to see them.

Spiritual heart of San Salvador

Archbishop Romero is buried in San Salvador’s Catedral Metropolitana. 250,000 people attended his funeral, about 5% of El Salvador’s population in 1980. It was a convulsive event though the war had many more years to run. His tomb is covered by a somber brass sculpture created by Italian artist Paolo Borghi on the 30th anniversary of his death.

When I stepped outside the cathedral onto the Plaza Barrio I could sense the energy of a city that has moved away from a divisive past to an energized present. Construction scaffolding, hammering, drilling, and attendant sounds of work enveloped me.

The new Biblioteca Nacional occupies one side of the plaza in a gleaming white building that the government described as a “cathedral of knowledge and learning”. Open 24 hours a day it is the largest library in Central America.

Latin American version of Singapore?

The Palacio Nacional is President Nayib Bukele’s residence. Taxi drivers, shopkeepers, and people I chatted with said the same thing about him: his strict anti-crime policies have led to a safe environment for the first time in anyone’s memories. Crime is way down and people are enjoying the freedom from that fear. The president has indicated a goal of turning El Salvador into a Latin American version of Singapore.

At the stylish Museo Nacional de Antropologia de David J. Guzman, I got an overview of the country’s progress from Maya times through the colonial period to modern times. The murals on the ground floor didn’t hold back: scenes of torture, murder and rape were depicted. On the second floor is a life-sized Maya sculpture of Xipe Toltec, the flayed one, so named because he wears the skin of a sacrificial victim. It dates from around 1000 AD. Nearby is a Maya stone disk of jaguar head from 250-900 AD.

Hearty, robust cuisine

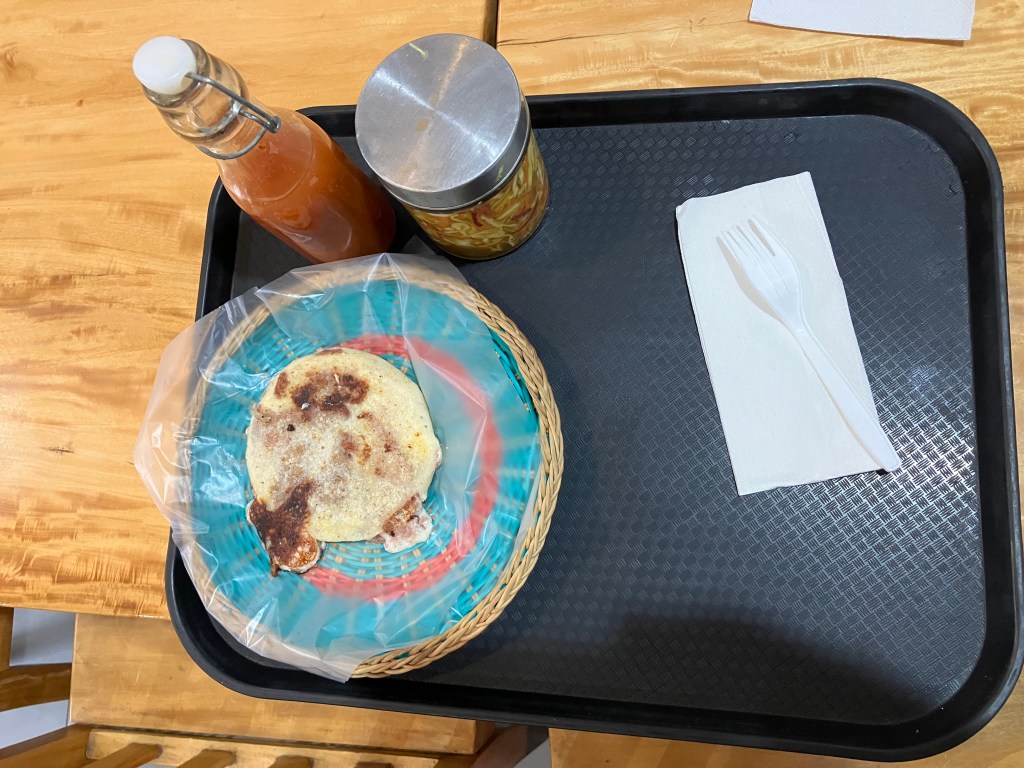

I loved Salvadoran cuisine. The national dish of El Salvador is pupusas, grilled flour and corn meal mixed with cheese and refried beans. They are served with a pickled cabbage relish and a tomato sauce. I enjoyed watching them being made, women’s hands slapping them into shape and onto hot grills. At Tipicos Margoth restaurant I feasted on pupusas, chorizos, empanadas, and quesadillas, which is a sweet cheese cake. I washed it down with a refreshing cinnamon horchata.

Music to chill by in a now chilled city

One evening I visited a popular jazz bar, The Balance, in the Colonia Escalon district. The music alternately soothed and seethed and the open-air bar was packed. A couple invited me to join them at their table and soon I was in a spirited conversation. They told me about El Salvador’s journey away from a divisive civil war and a country where gangs ran rampant. Things are so much better now, they said. Safe streets with companies like Google setting up operations. They added that costs are high and they have to worry about inflation and affording the good things in life that we all aspire to. In El Salvador, daily choices are not life and death anymore.

As I listened to the persistent rhythms of the music with a gentle breeze wafting through the bar of energized, gregarious patrons, I thought of how things had changed so much for the better here and how much Salvadorans deserved the brighter future that now seemed more certain than ever.

Pocket Guide

Where to stay: Hilton San Salvador excelled: large rooms, friendly staff, a short walk to numerous restaurants.

Where to eat: Tipicos Margoth for a wide selection of great Salvadoran food for a reasonable price.

Where to listen to music: The Balance has jazz bands playing on its terrace. The food is great too.

What to buy: Sopresas, miniature scenes hidden within clay eggs. I bought some for myself.

Best tour company: Grupo 3 Tours is one of the best tour companies I’ve used in the world. Helpful, friendly, punctual, top-notch.

Published in August/September 2024 Asian Journeys magazine

Leave a comment