We have heard the news about Hong Kong Disneyland’s missteps in trying to connect with its Chinese target audience. To have shark’s fin or not on its menu? Trying to get the park Feng Shui right. Alledgedly, rude staff. First, too few visitors. Then, over Chinese New Year too many. To the point where they had to lock the gates to hundreds of ticket holding visitors. Photos showed tourists scaling Disneyland’s fences to get inside. The managing director of Hong Kong Disneyland, Bill Ernest, apologized to the people of Hong Kong and China. “We are still learning in this market,” he said. “This is our very first Chinese New Year, frankly.” Hong Kong Chief Executive Donald Tsang said, “We feel disconsolate, but we have learnt a lesson.” Legislators in the territory feel the incident has damaged Hong Kong’s international image.

Yet, in Asia, there are very successful local theme parks who connect culturally with their target audience and produce smiles instead of headlines.

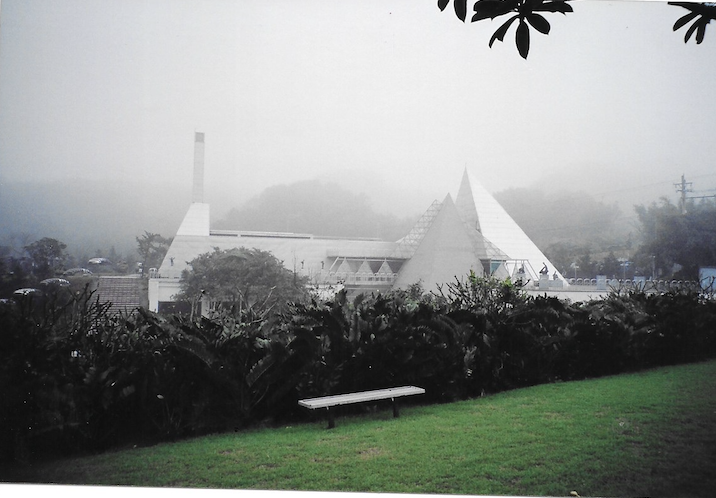

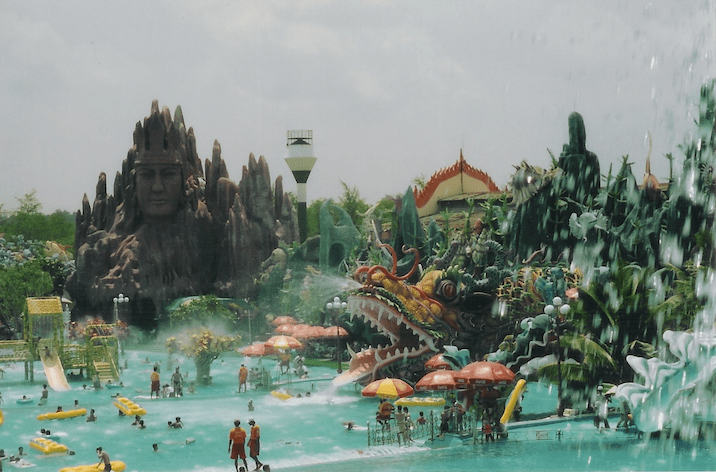

One such theme park is Suoi Tien, outside of Saigon. Its attractions are decidedly un-Disney in their make-up but their appeal is unmistakable.

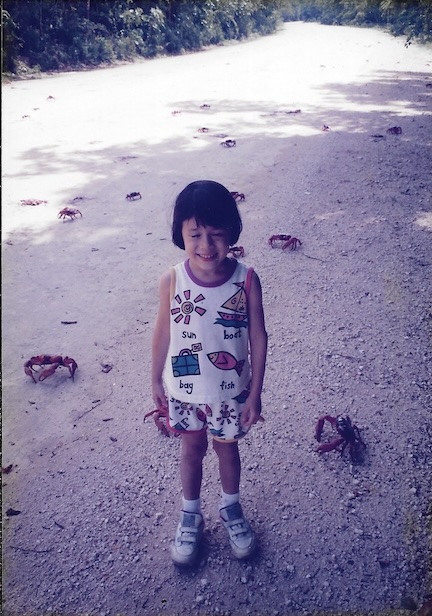

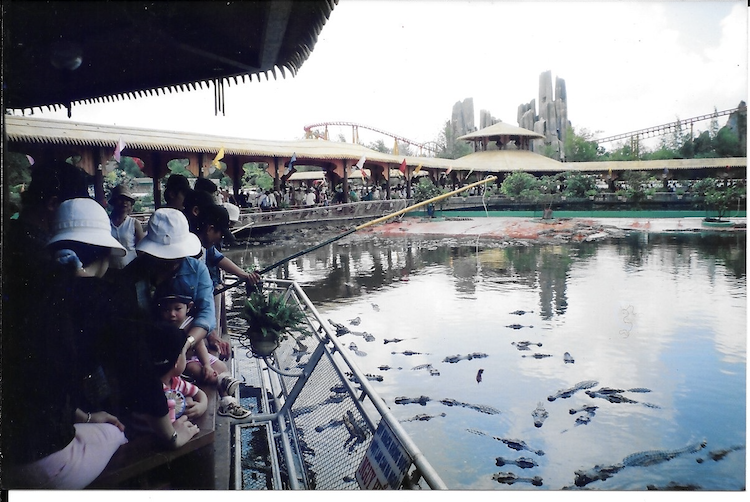

For example, at their “Kingdom of Crocodiles” attraction, I went “crocodile fishing”. For 15 cents I rented a bamboo pole with lump of raw meat tied to a string at one end of it and dangled it over a group of hungry crocs, mouths wide open in anticipation. They snapped. I pulled it away. They snapped again. I pulled it away again – until inevitably they won “the game” and ate. Thankfully, not my fingers and hands as well.

In Western terms, “Crocodile fishing” may not be politically correct – but based on the excited crowd I saw, it’s certainly spot on in Vietnam. Hong Kong Disneyland might not have an attraction like this one – but they could certainly learn from a park like Suoi Tien on how to bond with its target.

At nearly the same size as Hong Kong Disneyland, Suoi Tien’s appeal lies in offering attractions that are culturally unique to Vietnam. Like the massive public swimming pool called Tien Dong Beach. Surrounding it are mythical hills and palaces, a massive mist-spewing dragon and dominating the pool, park, and flat surrounding countryside a mountainous likeness of King Lac Long Quan, the mythological founder, with his wife Au Co, of the Vietnamese people. Yet this indigenous version of Mount Rushmore is a kind of Matterhorn ride – I hopped on a yellow raft and slipped and slided through the emperor’s head until I emerged wet and happy from a giant fish’s mouth.

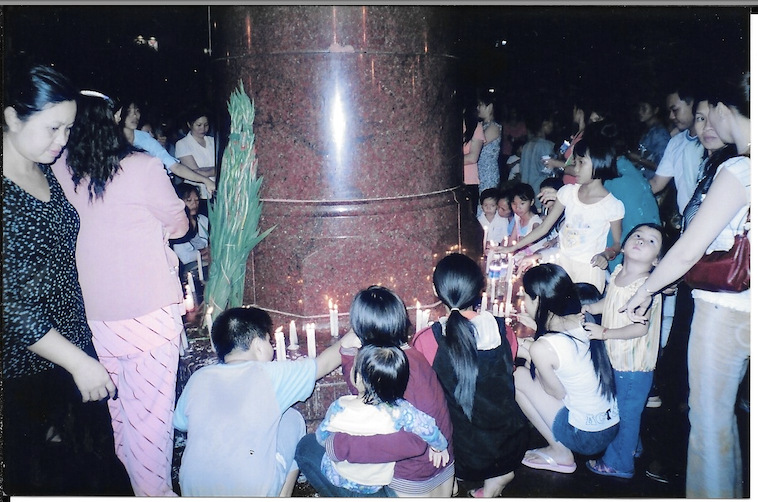

But my Vietnamese history and cultural lesson didn’t end there. There is a giant statue of the Trung sisters, riding elephants on their way to defeat the Chinese in the 1st century. There is the Phoenix Palace where I visited the 12 levels of hell, a local version of Pirates of the Caribbean – after the pirates had passed to the “other side”. I descended into a dungeon where I saw some neat tortures: somebody getting sawed in half and put back together again; another being eaten alive by a hairy monster; a body squeezed into a large wooden basin and pummeled like a bunch of grapes being turned into wine.

Then I tried the Palace of Heaven nearby. The re-creation of an emperor’s court had it all: a stern emperor and court officials; beautiful ladies-in-waiting and in one tableaux, mannequins dressed as ghost princesses, swinging angelically from wires.

The adventures all have a Vietnamese theme that is relevant to its target as, say, the “The Haunted Mansion” or “Space Mountain” rides are to the visitors of Disneyland.

At Suoi Tien there was a more participatory attraction where I went down a small dingy elevator and “attacked” the “Citadel” in the ancient capital of Hue through a hidden fortress tunnel. “Defenders” of the palace “slapped” my legs as I passed deeper into the fortress.

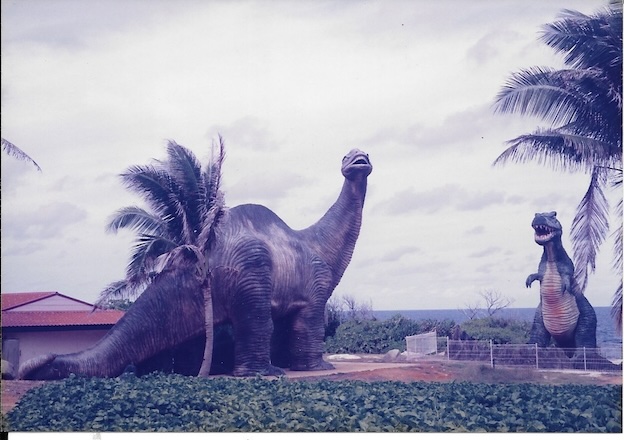

There were also prosaic attractions like a rollercoaster, ferris wheel, paddle-boating, aquarium, small zoo and bonsai “forest”.

And less prosaic ones like the tent with the “freaks” exhibit. Some of the wonders preserved in alcohol were Siamese pigs; a two-headed calf; a calf with six legs; a chicken with a very, very long neck.

Everywhere there were crowds and long lines – and lots of happy faces. Like Hong Kong Disneyland, Suoi Tien is a big favorite of out-of-towners, coming to Saigon for a visit. Near the end of my visit I came upon the Heavenly Palace. I’ve never been a big fan of “dressing up” in costumes and having my photo taken. But in this Hue meets Las Vegas meets Anaheim attraction I couldn’t resist. So, for a few minutes I wore the headgear and robes of a Vietnamese emperor and had my photo taken on a mock-up of a throne.

While I certainly didn’t feel like a king, I took away from my day at Suoi Tien rich and culturally unique memories. Not repackaged ones sent from distant shores. Now Hong Kong Disneyland could certainly learn from that.

Published in South China Morning Post, September 13, 2006