The highest point of my trip to Tibet is the Kharola glacier on the road from Lhasa to the province’s second largest city, Shigatse. At 5,500 meters, the air is thin – a short jog winding me – but the scenery rich. Poles topped by yak hair and wrapped with flapping prayer flags flank a simple white stupa that has as its backdrop the glacier draped over a craggy mountain while outlined by a sky of such an extraordinary cobalt blue that you want to lick it. Literally.

OUT OF THIS WORLD YET WITHIN IN

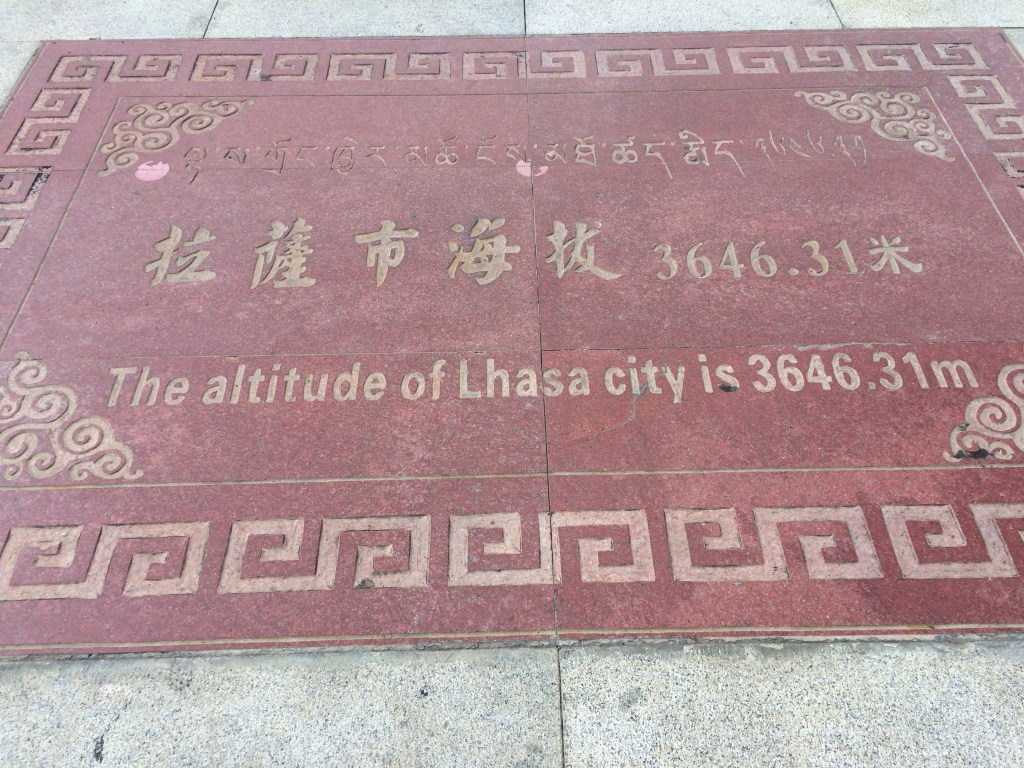

Tibet is a place that feels out-of-kilter both with the country it sits within as well as the earth it sits upon. The flight to Tibet teases you as it soars over the Himalayas, icy peaks defiantly punching through cloud cover while far below remote, deserted roads struggle to find a path in the barren plateau. When the Air China flight lands in Lhasa, the disembodied voice on the intercom says to be careful of altitude sickness. At 3,656 meters that warning resonates with me.

THE ALTITUDE CAN BRING YOU DOWN

While I didn’t experience altitude sickness on trips to Bhutan, Nepal or the altiplano of Peru and Bolivia, I realized it is a risk. It seems to strike at whim. Diamox, a medication effective at preventing it, works for me. While I vowed to take it very easy on my first day, Lhasa’s kinetic energy and otherworldliness, pulls me forward. Fortified by a lunch at the atmospheric House of Shambala restaurant I walk more than 20,000 steps. I experience sunset on the rooftop of the Tibetan Family restaurant over a dinner of fried yak-filled momos. The diminishing light of day illuminates the nearby golden canopies of Johkang Temple. Upon my return to the Gang-Gyan hotel, people in the clinic off the hotel’s lobby suck on oxygen from tarnished tanks while a nurse with crossed arms stands nearby.

LHASA’S SPIRITUAL AND COMMERCIAL HEART

The spiritual and commercial heart of Lhasa is the Johkang Temple and the adjacent Barkhor Square, ten minutes stroll from my hotel through twisting, narrow alleyways. A hive of religious fervor, to get onto the square requires passing through a gauntlet of very tight security. Omnipresent cameras on rooftops and along the eaves of buildings watch everyone. The security checkpoints have metal detectors, X-ray machines and card readers that capture locals’ identity information. Elite SWAT squads control these checkpoints while scattered around the square small squads of police in full riot gear stand at the ready. Their presence provides an ominous sense of the Chinese government’s heavy hand and a recognition that the surface calm is perhaps superficial.

On Barkhor Square I follow the pilgrims’ circumambulation around the Johkang Temple, passing restaurants, tea houses offering Tibetan butter and sweet tea, shops selling prayer flags, beads and other religious items, and antiques of various authenticity. The effect is an ever-moving, ever changing kaleidoscope of people with different poses, emotions, hopes, prayers, despair, physical conditions, and triumphs of sorts moving like a human tide clockwise around the temple and wondering if their life’s lots might change en route – or ever. It’s as turbulent as a Tibetan sky. A scrum of people surrounds a one-legged pilgrim who slams metal bricks together before prostrating himself on the ground. Then he lifts himself up and repeats the process again a few steps further on. It’s easy to hook onto the devotees’ tide and get pulled into their mania. Maybe the thin air helped —oxygen deprivation giving a light-headed perspective on the scene, like lining up a shot through fisheye lens for a distorted view of the world.

MAGNETIC “HOUSE OF MYSTERIES”

King Songtsen Gampo started building the Johkang Temple in 652 to honor his Chinese and Nepalese wives. Known in ancient times as the House of Mysteries it was finished nearly a thousand years later in 1610 during the reign of the 5th Dalai Lama. Two giant incense burners in the front and rear of the temple help give Lhasa its distinctive aroma.

Just outside and within the temple the fervor approaches fever pitch, dozens of people prostrating themselves then lifting themselves up in hope before throwing themselves down again in repetitive demonstrations of piety. The crush inside is driven by the determination that their prayers be heard. Blessings by monks are seemingly cursory as they try to move the crowd through. I don’t understand what people are asking for but I do recognize hope as a universal need. The temple’s magnetism keeps me close to it and the square during my Lhasa visit. That evening I dine on grilled mushrooms and ginger carrot soup at the packed Makye Ame restaurant overlooking the rear of the temple. The yellow-painted building it is in was the 6th Dalai Lama’s palace and named after his mistress. He wrote a poem about her here.

ONE OF THE WORLD’S GREAT PALACES

About 1,000 meters away is the administrative heart of Tibetan Buddhism, Potala Palace, the residence of Dalai Lamas until the 1959 Chinese invasion ended the Tibetan uprising and forced the 14th Dalai Lama into exile. The 5th Daiai Lama started building it in 1645 on the remains of an earlier one from 637 by King Songtsen Gampo. Its location is strategic: between the influential Drepung and Sera monasteries, and Lhasa’s old city. It took three years to build and another forty-five before the interior’s completion in 1694.

It’s a massive edifice: 400 meters from east to west and 350 meters north to south with stone walls around 3 meters thick in most places and 5 meters thick at the base. It’s more than 117 meters high on top of Red Mountain and rises more than 300 meters above the Lhasa Valley floor. It has over 1,000 rooms and some 200,000 statues. The areas painted white are the administrative parts of the palace, while the red painted ones are where the Dalai Lamas resided and ruled. Assembly halls, shrines and thrones of the past Dalai Lamas are located here, including the cave where King Songtsen Gampo meditated. Gilt-covered roofs reflect the intermittent sparkling sunlight giving an unusual sense of lightness to such a sturdy structure. It was lightly damaged during the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s premier Chou En-Lai having protected it.

One of the world’s great palaces, perhaps France’s Versailles or Russia’s Winter Palace come close to matching its splendor. I pass through a number of security gauntlets before entering. At the palace’s base, flowers are in full bloom — Tibetan summer and spring converging into a single, very short season of vibrant colors in a landscape that is dour and forbidding most of the year. Potala Palace tickets are timed and visitors move quickly up the stairs in the thin air to meet the various deadlines. Unlike other museum-like grand palaces, it is a place of devotion. Tibetans prostrate themselves in front of shrines and religious relics. Security brusquely moves them along.

SPINNING PRAYER WHEELS TO WIN AT LIFE’S LOTTERY

The various Dalai Lama thrones give an indication of their personalities and styles of ruling. Many are modest elevated platforms to preside cross-legged over subjects. The 6th Dalai Lama was probably the most controversial because of his notorious lifestyle as a womanizer and magician. He has by far the largest throne. The second largest throne belongs to the current Dalai Lama. I also notice the size of his throne at Norbulingka Palace, known as the summer palace. His throne of gold with silver steps is the largest of the Dalai Lamas with residences there. After exiting Potala Palace down steep steps in the back I come to an endless line of prayer wheels which devotees spin — for luck or health — to help win in the lottery that is life. The sound of the spinning wheels rubbing against aging wood creates a humming that rises in the air to create another dimension of etherealness to the palace.

PROTECTION AGAINST NIGHTMARES

If the Potala Palace and Johkang Temple are the administrative and spiritual hearts of Tibet, Sera Monastery is the intellectual heart. Founded in 1419 the sprawling monastery sits at the foot of the mountains at Lhasa’s edge, a remote nunnery high on a hill above it. Parents take their children here to inoculate them against nightmares. After a monk’s blessing ashes are smeared on their noses and they walk away with smiling faces — safe in the knowledge that sleep will be just blissful dreams. In a sun-dappled courtyard nearby dozens of monks in pairs, one standing and one sitting, debate with vigor. The standing monks, fiddling with prayer beads and stamping their feet and clapping their hands, hurl Buddhist doctrine questions from the Five Major Texts at the sitting monks. The questions are theological ones with rhetorical twists and the gift of constructing eloquent responses prove the intellectual rigor of the monks. Eventually, they switch places. This sparring is mesmerizing to watch, like mental martial arts. The voices rising in challenging tones create a strangely melodious sound like binaural beats from a Haight-Ashbury hippy store. During the 1959 revolt, hundreds of monks were killed here and survivors set up a parallel monastery in exile in Sera, India.

BREATHTAKING’S DOUBLE MEANING

The Lhasa to Shigatse road gives an indication of Tibet’s magical landscape and breathtaking vastness. Just outside Lhasa a tunnel reveals the Yellow River, one of China’s and the world’s longest, beginning an over 5,000 kilometer journey to the sea. As the van climbs switchbacks, proud owners display regal Tibetan Mastiffs at scenic turnoffs and charge 10 yuan to have a photo taken of them. The Khamba La pass at an elevation of 4,998 meters overlooks Yamdrok lake. The scimitar-shaped lake has a turquoise colour transforming chameleon-like in front of you as if reflective of volatile moods. Such a sacred sight at such an elevation brings a double meaning to the word breathtaking. It’s forbidden to eat the abundant fish from its crystalline, holy waters. At the shore Tibetans charge for sitting on decorated yaks with stoic demeanors.

In a few hours, past the Kharola glacier, is the city of Gyantse. The Dzong, fortress, lords over the city. I visit the Penchor Chode monastery, guarded by red, parapet-topped walls. The monastery’s main building, built between 1418 to 1425, is closed that day as the monks are engaged in a secret chanting ceremony. Having watched burly monks from the Yellow Hat sect chant at Ramoche temple in Lhasa I can imagine the intense, rumbling sound as the prayers emerge deep from their chests.

WHERE THE BRITISH INVADED TIBET

The Kumbum, a type of pagoda, next door was founded in 1497 by a Gyantse prince. It has nine levels, 108 gates and rises 35 meters. It has 76 chapels and is filled with entrancing Buddhist religious paintings that remind me of the legendary Mogao caves in Dunhuang. The Gyantse Kumbum is the most famous in Tibetan Buddhism. I climb ladders to reach the highest level, heavily lidded, all-seeing eyes painted at the top. The fortified red walls of the monastery seem to reach out finger-like to the forbidding heights of the nearby Dzong that protects it. The Dzong was the site in 1903 of a fierce battle between Tibet’s best troops and a colonial British invasion force known as the Younghusband expedition after Colonel Francis Younghusband. The battle was overseen by Brigadier General James Macdonald under the auspices of the Tibet Frontier Commission. Sent by the Viceroy of India Lord Curzon, the invasion was part of the 19th century “Great Game” between Great Britain and Russia for influence in Central Asia. Great Britain preemptively invaded Tibet to keep it out of Russia’s hands. After Gyantse fell, the British went on to seize Lhasa and dictate the terms of the 1904 Treaty of Lhasa where the Chinese government agreed to not let any other country interfere in Tibet.

PANCHEN LAMA’S HOME

After a night at the garishly decorated Gesar Hotel in Shigatse, I visit the Tashi Lhunpo Monastery. Founded in 1447 by the 1st Dalai Lama, this is the home of the Panchen Lamas, Tibetan Buddhism’s second highest rank. The current Panchen Lama is only 28 years old. The Gorkha Kingdom sacked the monastery when they invaded in 1791 but they were quickly pushed out by a combined Tibetan and Chinese army. It was also damaged during the Cultural Revolution. The monastery climbs up the mountain and is protected by a nearby Dzong. Inside there is a vast assembly hall, now empty, that I can imagine being filled with chanting monks sitting cross-legged. At a temple, the guide points out what looks like a gold-covered statue of the previous Panchen Lama with a yak hair wig and a golden bell in his uplifted hand. Only it isn’t a statue but the mummified body of the lama, deceased since 1989.

The train back to Lhasa follows the Yarlung Tsapo River Valley. When the river leaves the Tibetan Plateau, it carves a canyon deeper and longer than the Grand Canyon — one of the world’s great sights few people get to see.

FROM SUMMER SUN TO STORMY SKIES

On my last night, I join a couple at Po Ba Tsang restaurant, featuring Tibetan dancing. The dancing strikes me as something from one of the Central Asian stans — aggressive leg thumps creating mini earth tremors on the wooden floor. Dinner is momos floating in a broth with fried yak cheese on the side. Crisp Lhasa beer helps down it.

That night I see Potala Palace perched high above the vast Potala Square on the opposite side of Beijing Middle Road. Potala Square has dancing musical fountains, a billboard featuring past and present Chinese leaders and the angular Tibet Peaceful Liberation monument guarded by soldiers. Lit against the blackest of nights, thick clouds obscuring stars, Potala Palace is revelatory, apparition-like. While my Tibet visit is in the midst of the summer rainy season I experience warm, mostly sunny days during my stay. It is ironic then that on my walk back to the hotel a nightmarish thunder and lightning storm sky splits the sky and spits hail. I wish that a Sera Monastery monk had put some nightmare inoculating ash on my nose too.

A few weeks later during an Uber ride to New York’s LaGuardia airport, I ask the driver where he is from. “Tibet,” he says. I tell him what a coincidence that I got him for my driver as I had recently been there. He smiles at me in the rearview mirror and says, “Karma.”

TRAVEL TIPS:

Restaurants:

-Tibetan Family Kitchen

-Makye Ame Tibetan restaurant

-Po Ba Tsang restaurant

-House of Shambala restaurant

Hotels:

-The Gang-Gyan Hotel in Lhasa’s old city has quirky touches: a humidifier that looks like a character from an animated cartoon and motion sensor activated hallway lights that provide light where you are and pitch darkness everywhere else.

-The Gesar Hotel in Shigatse is garishly decorated like a Disney-fied version of yurt fit for a khan.

Tibetan Travel Permit:

A China visa gets you into the country, but not Tibet. You’re not allowed to travel alone or even visit a temple without an official guide. A tour company can get you a Tibet Travel Permit. Mine is checked four times before I enter Tibet. It has a holographic-like stamp stapled to a paper with my details.

Altitude Sickness:

Consider how to prevent altitude sickness before your trip. Diamox, a well-known medication, works. The supplement Ginkgo Biloba supposedly helps. Going to a high elevation in phases allows the body to adjust. I stay two nights in Chengdu at 1,640 meters before travelling to Lhasa. My uncle, a doctor with high altitude climbing experience, notes that going straight from sea-level to Tibet will almost certainly get you sick.

Photography:

In Lhasa, photography isn’t allowed at the temples and monasteries. Outside Lhasa it is allowed but sometimes at a very high cost. At Shigatse’s Tashi Lhunpo monastery, some of the temples requested a 150 RMB photography fee.

Getting there:

Flights to Lhasa leave from a number of Chinese cities. My round trip airfare on Air China from Chengdu during the peak summer season is a pricey US$577. The flight is 2 hours.

Published in Asian Journeys magazine, October-November 2018