Bangkok’s reputation as a shop till you drop destination is so well known it’s practically a meme. From Siam Paragon and Central World in Ratchadamri to Chatuchak weekend market to the newish Icon Siam on the Chao Praya river, listing them all would dwarf a Yellow Pages directory; visiting them all would be more tiring than sprinting up the side of the Grand Canyon.

Inspiring art to inspire shopping for art

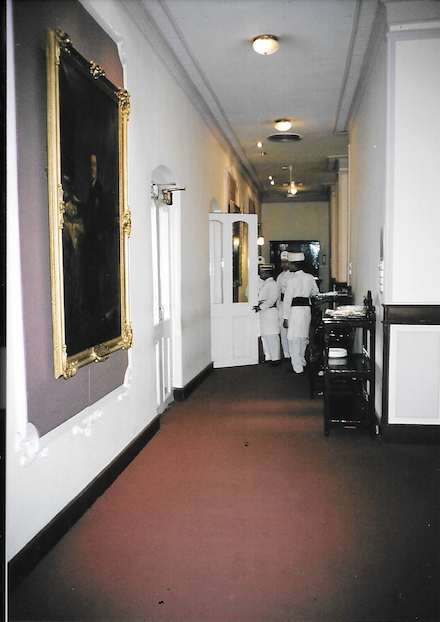

What is less well known is that Bangkok is a destination for art lovers who love to shop for art. That shouldn’t be too surprising since Bangkok is a center of art from the traditional to contemporary. If art is your focus – and it is mine – then starting it from a hotel with expertly curated artwork gets your mind in the right space before deciding what will occupy a space in your home. The Anantara Siam, designed by leading Thai architect Dan Wongprasat, has a jaw dropping palatial lobby. The mural on the grand staircase landing of a traditional royal scene in hues of gold and red and the mandala painting on the sweeping ceiling by the late artist Arjarn Palboon Suwannakudt, gives the expansive space the feeling of a living, breathing palace that you want to linger in. And would certainly like to stay at.

Artful champagne brunch fuels my search

The Sunday champagne brunch to fuel my search for art was so rich – and enriching – I almost called off the search. After the lobster thermidor, foie gras, fresh scallops, raw oysters, dessert bar and glass after glass of champagne I was feeling a little too comfortable to brave the rigors of art appreciation. But a cup of espresso finally got me off the all too comfortable dining room chair.

Contemplate life while contemplating traditional art

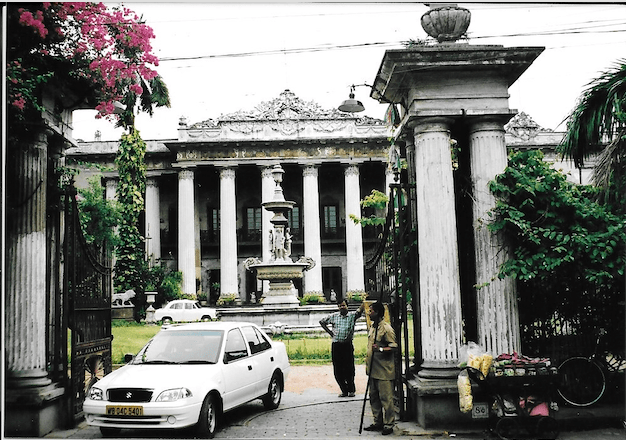

Armed with a Bangkok Art Map that I got from the Anantara Siam’s concierge I started my art shopping excursion at Suan Pakkad Palace on nearby Sri Ayutthaya Road. There was nothing to buy at this museum but plenty to inspire me. The palace, once the home of Prince Chumbhot of Nagara Svarga and his consort, features a collection of artwork and antiques in eight houses that are some of the best examples of traditional Thai architecture in the city. The murals, sculptures, and art you see while sliding in your socks across polished wooden floors started the process of deciding what would work best in my home. What I saw there gave me ideas as to what antiques I would like to get. And I know that one of the most renowned centers for antique shopping in Asia is The River City Bangkok mall on the Chao Praya River.

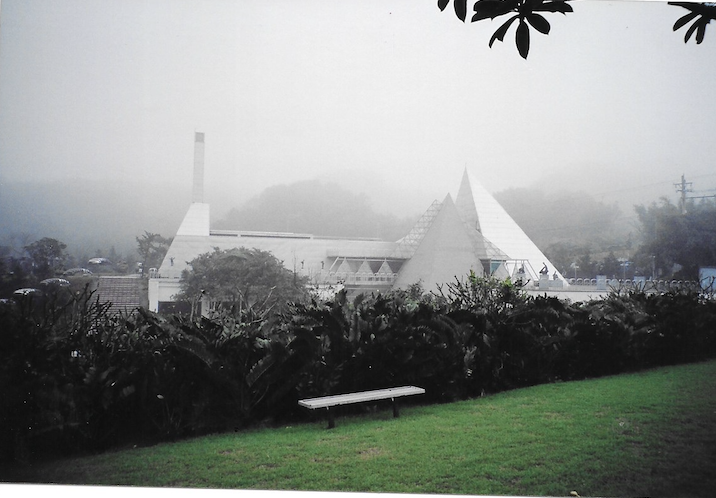

Echoes of Frank Lloyd Wright

My next stop was the Bangkok Art and Culture Center. It’s on the opposite end of the art spectrum from the Suan Pakkad Palace. An eight-story venue for contemporary art and shops selling hip crafts and gifts it attracts a crowd poked and provoked by its art. I went to the top floor to see the wonderful Royal Photo Exhibition, “Photos Wonderland,” and then worked my way down the spiral walkway that took me from one floor to the next for further art contemplation. It reminded me a bit of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York with its top down spiral walkway. One of the shops, BKK Graff, sells cans of spray paint so that you can graffiti a space. Hopefully, not your home.

Talked about art for your walls

A short walk from the Anantara Siam are three galleries that are among Bangkok’s best for contemporary art. Le Link Gallery, Tonson Gallery, and Nova Contemporary all feature contemporary artists whose art can dominate a wall and become a talking piece for visitors. Or yourself. Displayed at the Le Link Gallery were the brightly coloured Magenta Blues Artwork by German artist Ingeborg Zu Schleswig-Holstein.

Before returning to the hotel I had a drink at the nearby Smalls Bar, chockablock with art. It’s rated by CNN Travel as one of the top bars to visit in Bangkok. All the art displayed in the three-story quirky bar is for sale.

From fine arts to culinary arts at The Spice Market

After a day launched with a great meal it was time to end it with one. On the way into the hotel lobby I passed statues of water sprites surrounded by water lilies. Their presence is a reminder that you are entering a special world.

The Anantara Siam’s The Spice Market is one of the finest Thai restaurants in Bangkok, helmed by award-winning Chef Warinthorn Sumrthlphon.

The ambience of the restaurant puts you in the right mood to savor the food. With a polished teak wood décor, tables topped by Carrera marble, and cotton napkins and pillowcase coverings by Jim Thompson, it is a luxurious setting.

And the food lives up to the décor. The ingredients are sourced locally to ensure freshness. The fruits and vegetables are all organic. The curry pastes are from the kitchen of M.L. Thor Kridakorn, whose recipes are so famous that they grace the dining table of the Royal Family.

Some of the dishes I tried were the Tom Yam Goong, a spicy prawn soup perfectly flavoured with lemongrass; Larb Nua Pu Gab Goong Mae Nam Yam, crab meat salad and grilled river prawn; Pu Nim Phad Prig Thai Orn, crispy soft shell crab in peppercorn sauce; Kai Soe Rua Nua, northern style egg noodles in curry with chicken; and, Gaeng Kiew Warn Nua Toon Cab Roti, green curry with braised beef in coconut sauce.

No amount of description can do them justice. More chamber music than symphony with their focused and nuanced flavours each dish was a distinctive delight. The meal was so filling I couldn’t tackle dessert, much as I wanted too. Next time I’ll pace myself better. I have my eye on the Tubtim Krob, the ruby water chestnuts.

Only hotel in Thailand to offer sacred tattoo sessions

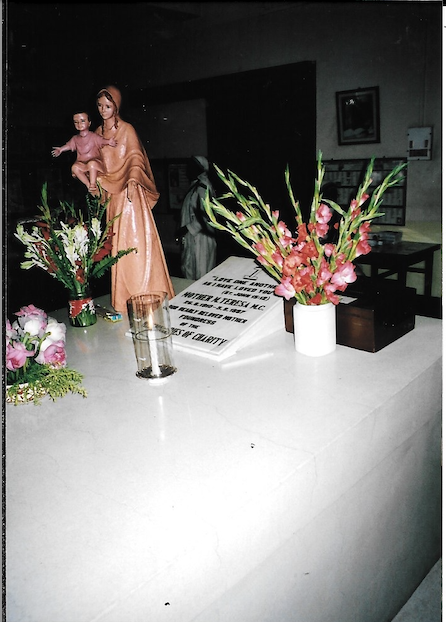

Anantara Siam’s commitment to art is more than skin deep. It is the only hotel in Thailand to offer private sacred tattoo sessions by Bangkok’s most famous Sak Yant master, Ajarn Neng Onnut. He has inked Hong Kong star Alex Fong and Hollywood ones Ryan Philippe, Jessica Bradford, and Brooke Shields.

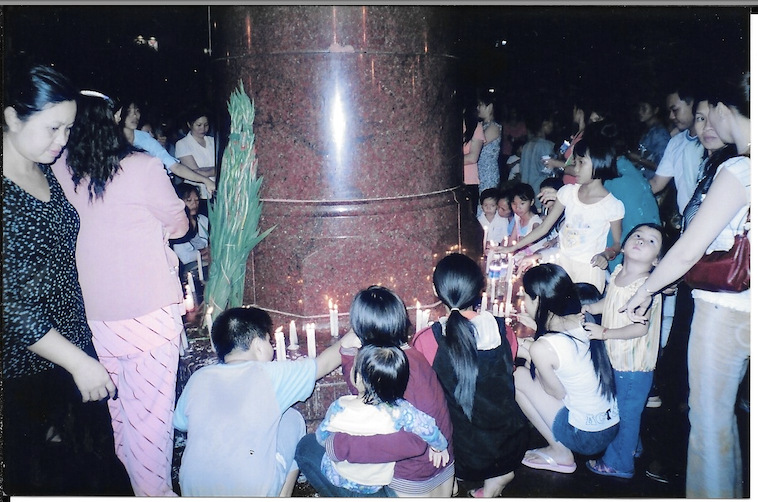

As one of the world’s most ancient, sacred traditions, to master Sak Yant means learning how to do the artwork for almost a thousand different images. To become a master Ajarn Neng learned how to read and write ancient Khmer and Pali scripts and memorise unique prayers and secret spells, chants and mantras that relate to the sacred tattoos.

His tattoo sessions at the Anantara Siam are private, either in a guest’s room or a private treatment room. The day before the tattoo he has a consultation with the guest where he learns about their life and goals before deciding on the correct Yant. Prior to the session and afterwards, Ajarn Neng performs a ceremony where the guest’s body and the art are blessed. That gives the wearer of the tattoo an emotional reminder of the experience that links the ink on their body to what it means to their life.

Leaving an indelible mark in more ways than one

A session with Ajarn Neng will leave an indelible mark on your spirit and your body. The Anantara Siam offers this unique experience so that you can get beneath the skin of Thailand for a richer appreciation of its culture.

The same is true of a stay at the Anantara Siam hotel. The culinary art of its kitchens, the prompt, warm service, and the art that embraces you in visual splendor when you enter the hotel will also leave an indelible mark; the kind of indelible mark we all want to experience and take with us wherever we go.

Published in Asian Journeys magazine, February-March 2020