Antigua: Three volcanoes surrounding a UNESCO Heritage Site

Antigua struck me as the legendary town of Macondo come to life. Its streets seemed to embody the mythical town at the heart of Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s novel “100 Years of Solitude.” Yes, I know that Macondo is set in Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s native Colombia and Antigua is in Guatemala. But its mystical feel and magnetic pull made me feel this UNESCO Heritage Site was in a place like no other, one I wanted to linger in for a while.

At the Heart of Guatemala’s History

Antigua is at the heart of Guatemala’s history. Ruled by the Maya from 1000 BC to 1524 AD, Guatemala was conquered by the Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado from 1523-24. Antigua was founded in 1543 to become the locus of Spanish colonial rule throughout Central America. A destructive earthquake hit in 1773 and many of its 38 churches as well as mansions, convents, and homes were badly damaged. While many weren’t repaired since then — those that were faced another deadly earthquake in 1976. The visible damage from the two earthquakes is one of the distinctive features of Antigua — a city that at its peak attracted the focus and funds of the unimaginably rich Spanish colonial power. Now, its candor is its charm, a city unafraid to reveal a few gray hairs and age spots that don’t detract from its glamor, even if its glitter is long gone.

Once a Backwater

Antigua became a backwater in 1775, when two years after the quake Spain moved the colonial capital to Guatemala City. And that’s where Guatemala’s history played out. Independence was achieved from Spain, then Mexico in 1823. A CIA coup against President Jacobo Arbenz happened in 1954. A deadly civil war occurred from 1960 to 1996 with a staggering 200,000 deaths. Now peaceful, Antigua is at the center of Guatemala’s efforts to attract tourists to a country that has been at the political center of Central American history for literally 3,000 years.

Fireworks over Antigua

I was eating Kaq’ik, a multi-layered spicy Maya soup from Coban at the charming El Adobe restaurant, the sound of a woman slapping tortillas onto a grill creating a soundtrack in the background. Explosive fireworks lit up the sky overhead. I went to the second floor to see the fireworks illuminate the night sky and the colonial skyline. Burst, crackle, and then descending colorful lights, fading in illumination as they approached the earth.

Pre-Easter Procession

Outside, I followed a large procession as it moved through the glowing cobblestoned streets, flanked by colonial-era buildings, homes, and churches. A scarlet red banner with a gold crown was held high and proud. Three mask-wearing women wearing red robes and white aprons and carrying torches led the way. Several dozen people shouldered a large float, called an anda, as they swayed down the street. When a man or woman peeled off from carrying the float, they were immediately replaced, a sense of strong community with the burden shared by all. On top of the float was a statue of Jesus, in a purple cassock with a scarlet sash. Jesus is depicted as struggling beneath the weight of the cross. A sculpture of a winged angel was at the front of the float and a lamb at the back. A half dozen musicians with drums, cymbals, trombones, and horns announced their presence as they slowly walked and played while following the procession.

I trailed the procession to its endpoint, the Catedral de Santiago, built in 1545 and ruined in the earthquake of 1773. All that remains is the parish church of San Jose, in what used to be the front of the cathedral. At the entrance to the cathedral was an alfrombra, an elaborate carpet made of sawdust, pine needles, fruit, vegetables, and flowers. After the procession and the band entered the San Jose church, I looked at the ruins of the cathedral, pillars with no roof to hold anymore, carved angels that were meant to gaze down on congregations, looking at no one now, exposed to the elements.

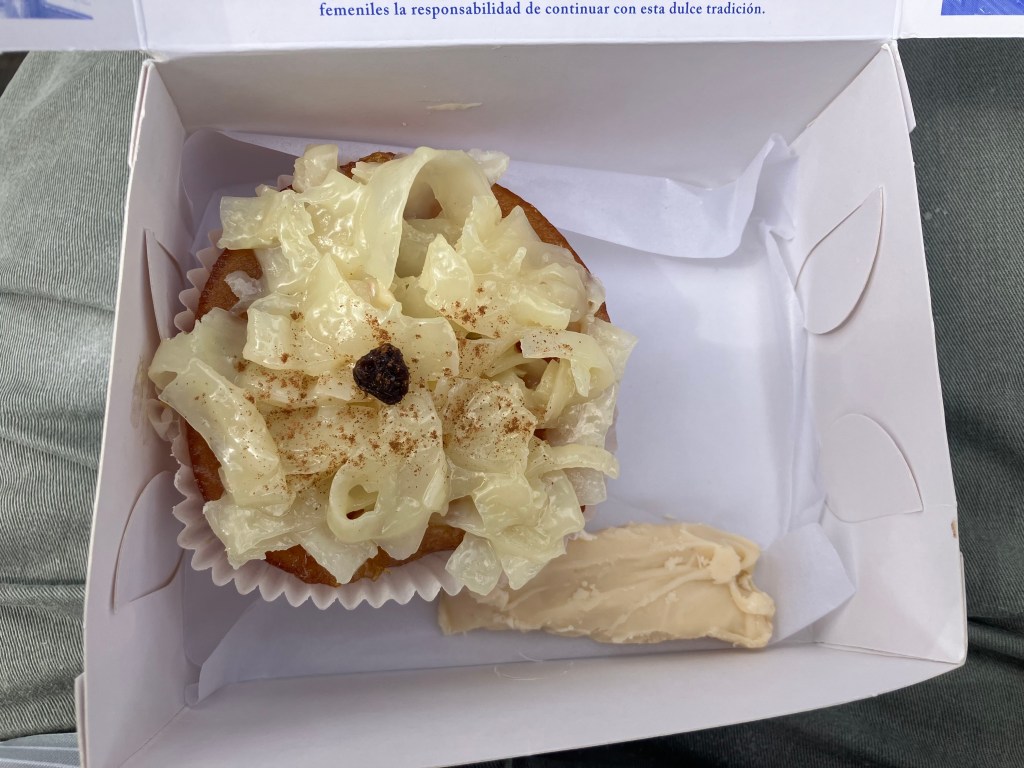

Traditional Pastries from Antigua’s Oldest Pastry Shop

Pastries from Dona Maria Gordillo were a sweet way to start many of my days here. Founded in 1872, the traditional pastries it serves are astounding – light, nuanced flavors with varying levels of sweetness across the topography of each piece. I would get them packed in a box and devour them in the Parque Central.

Parque Central – Social Nexus of Antigua

Jacaranda trees in bloom dropped purple petals onto the footpaths of Parque Central. Birds of Paradise with colorful, pointy beaks lined the flowerbeds. I sat near the central fountain where water streamed through the fingers and breasts of sculptural depictions of nymphs. Surrounding the plaza were some of Antigua’s finest colonial edifices. The Catedral de Santiago — the San Jose church part of it — was on one side, the elaborate white façade dotted with sculptures overlooking the plaza. The ruins weren’t visible from here.

The imposing Palacio de los Capitaines de los Generales was on another side. Built in 1549, it was once the capital of all of Central America. It is now a mind-blowing art museum known as MUNAG, Museo Nacional de Arte de Guatemala. The building itself is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. I spent several hours here seeing art from pre-colonial to the colonial era and to the Republican period. The stunning art pieces were beautifully displayed. I had a coffee at the Café Condesa at the Antiguo Colegio de la Compañía de Jesus, occupying another side of the plaza. I noticed that people at the café were more interested in each other and the people watching than their phones. The building was built in 1626 as a Jesuit monastery and college until the order was expelled in 1767. Six years later, the building was ruined in the 1773 earthquake. Now there are shops, cafes, and a cultural center.

I strolled past the 18th-century Palacio del Ayuntamiento to the Arco de Santa Catalina, built in 1694. This arch is perhaps Antigua’s most iconic monument. When you look through it, you can see one of the three volcanoes that surround Antigua, Volcan Agua. At any time of day, groups or individuals, from proud brides to friends proud of each other, are posing in front of it.

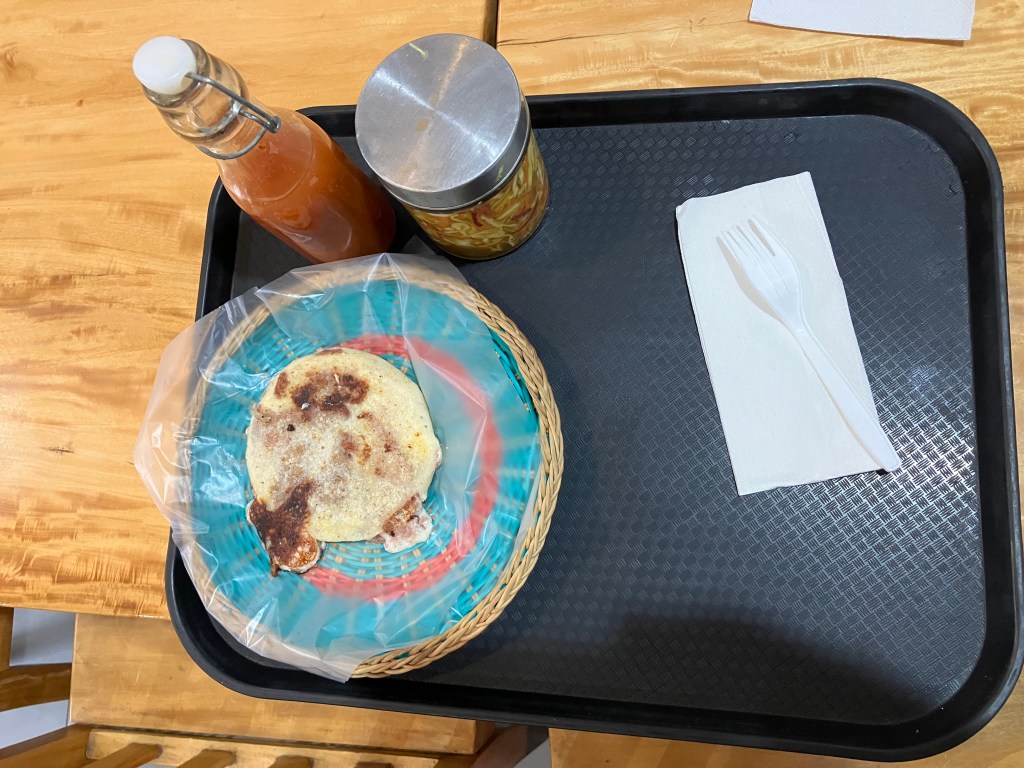

Maya Stews from Ancient Recipes

For lunch, I liked to eat Maya stews at La Cuevita de los Urquizu. Large earthenware pots contained Pepian Chicken (chicken and veggies in a piquant pumpkin seed sauce), jocon (green stew with herbs and chicken with tomatillos), kaq’ik (turkey stew), and other dishes I didn’t know the names of. It was a feast. And I was the only foreigner in the restaurant.

Guatemala History, Art and Culture on Display in Museums

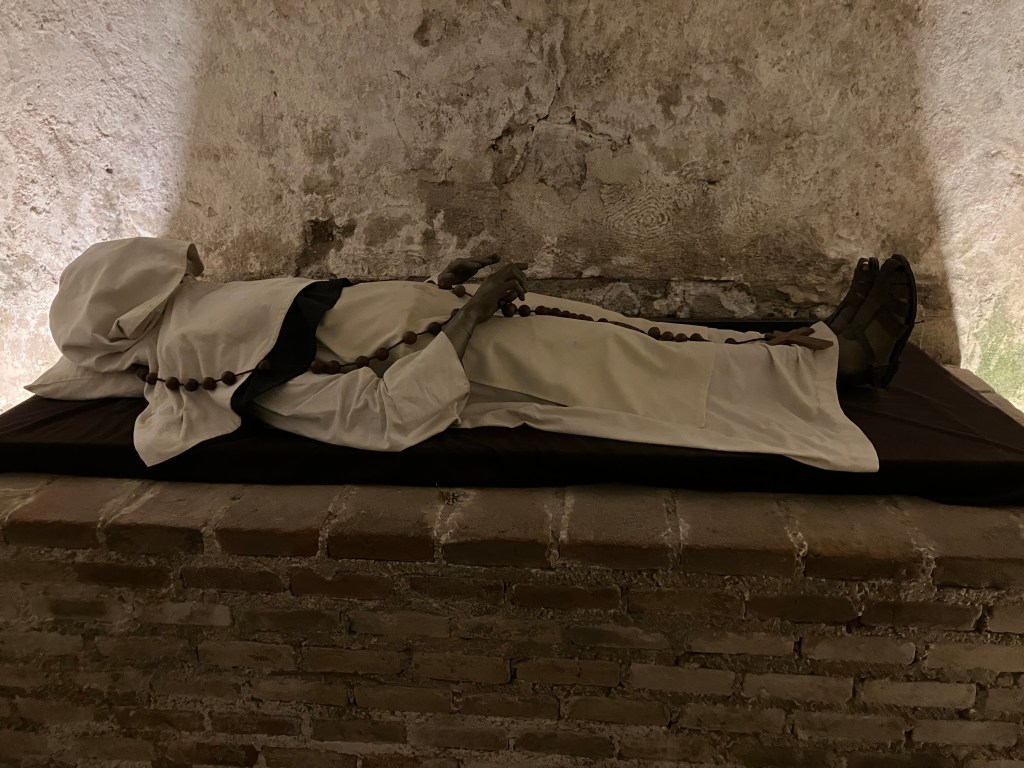

Antigua has some great museums. The Iglesia y Convento de Santo Domingo was a monastery founded by Dominican friars in 1542. Buildings on the site were rummaged for materials after the earthquake of 1773. The haunting ruins and restored buildings now house six museums: stunning silverwork at the Museo de Plateria; 16th-18th paintings and woodwork at the Museo Colonial; Maya stonework and ceramic at the Museo Arqueológico; Maya art juxtaposed with modern pieces at the Museo de Arte de Precolombino y Vidrio Moderno; traditional Antigua handicrafts at the Museo de Artes y Artesanias Populares de Sacatepequez; and a restored 19th apothecary shop at the Museo de la Farmacia. There’s also the ruins of the monastery’s church, candle and pottery maker workshops, and the Calvary Crypt, which houses a 1683 mural of the crucifixion. All of these museums and ruins are now part of the grounds of the atmospheric Casa Domingo Hotel, where I took well-needed breaks over coffee while working my way through the museums.

Colonial-era Churches Provide Spiritual Depth

Antigua is of course, famous for its colonial-era churches — intact as well as ruined — that provide spiritual depth to the city. Iglesia Merced, built from 1749 to 1769, was built with the thick earthquake-proof walls similar to the baroque churches in the Philippines. It’s a vibrant religious destination in the city.

At the Convento de Capuchinas, renovated after the 1773 earthquake, I got a sense of how the nuns lived. I strolled past an indigenous woman wrapped in colorful fabrics, through the markets where fruits and vegetables shimmered in the bright, though opaque light. At nearly every turn, one of Antigua’s looming volcanoes – Agua, Fuego, and Acatenango – stood sentinel-like, serene, almost omniscient in their quiet force.

Ruins from the 1773 earthquake, combined with partial repairs and renovations such as those at the Colegio de San Jeronimo and Iglesia y Convento de la Recoleccion, gave Antigua a haunting beauty that is both timeless and stuck in time. It wasn’t the spic n’ span over-polished look that some colonial-era cities have.

A Vibrant Nightlife

Antigua surprised me by having a really lively nightlife. Even Starbucks was a truly stylish hangout here. On the weekend, partygoers from Guatemala City, just an hour or so away, crowded into the city — and then into the bars and nightclubs. The restaurants and bars were north of Parque Central. After a few bottles of Moza beer, I slipped off a stool and headed back for the night.

Post-Sunset Fairytale Ambiance

I passed a woman in Parque Central, selling sparkling purple balloons that provided a fairytale-like ambiance to the post-sunset city. On my walk down the empty cobblestoned streets, soft echoes trailed me at every step. At the simple, elegant Hotel San Jorge by Porta I knocked on the heavy wooden door and was let in by the receptionist. I sank into a chair by the courtyard and let the crisp mountain air envelop me. Antigua, I decided, wasn’t just a city to see but a city to help you see yourself — ruminations via ruins.