Between the Space Needle and Pike Place Market

Between the Space Needle and Pike Place Market and at the heart of Seattle’s rock history, sits Belltown. I call it bella Belltown because the Italian word for “pretty” describes it well. Just an easy 26-minute walk separates the two tourist attractions, but you shouldn’t rush it because Belltown is a neighborhood worth lingering in.

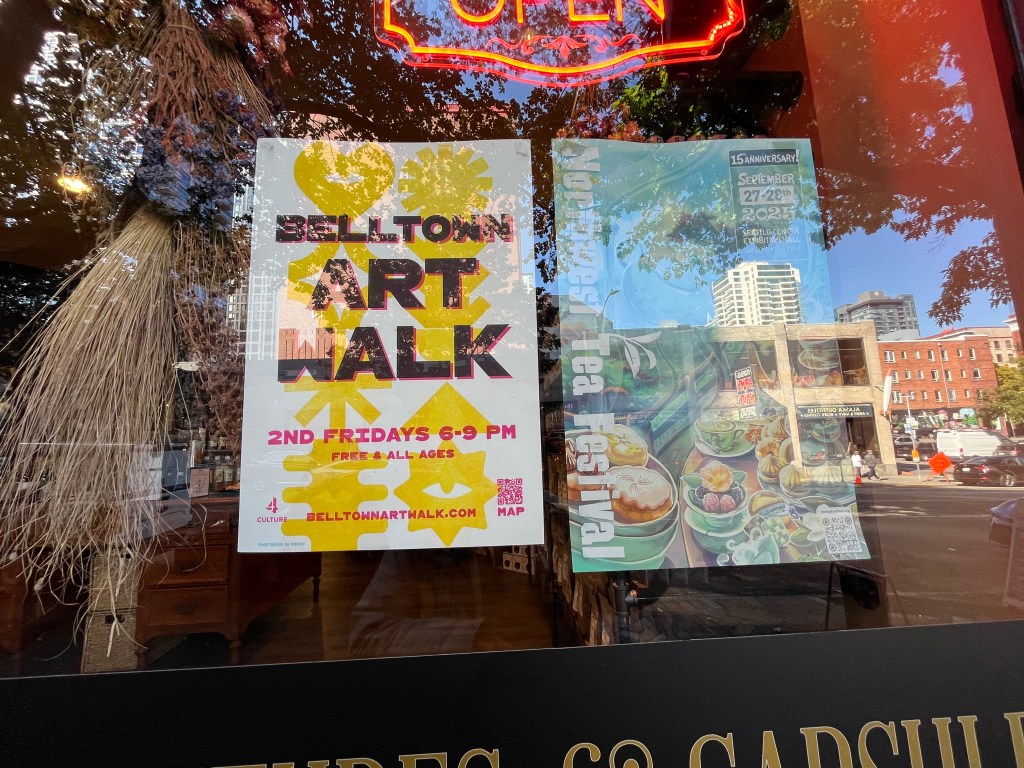

Belltown’s streets are filled with restaurants, cafes, bars, shops, and galleries, making this a place to browse. On the second Friday of every month is the Belltown Art Walk, where the galleries are open until 9 pm. Easily two dozen venues are involved in this regular event.

From where rock bands play to where they stay

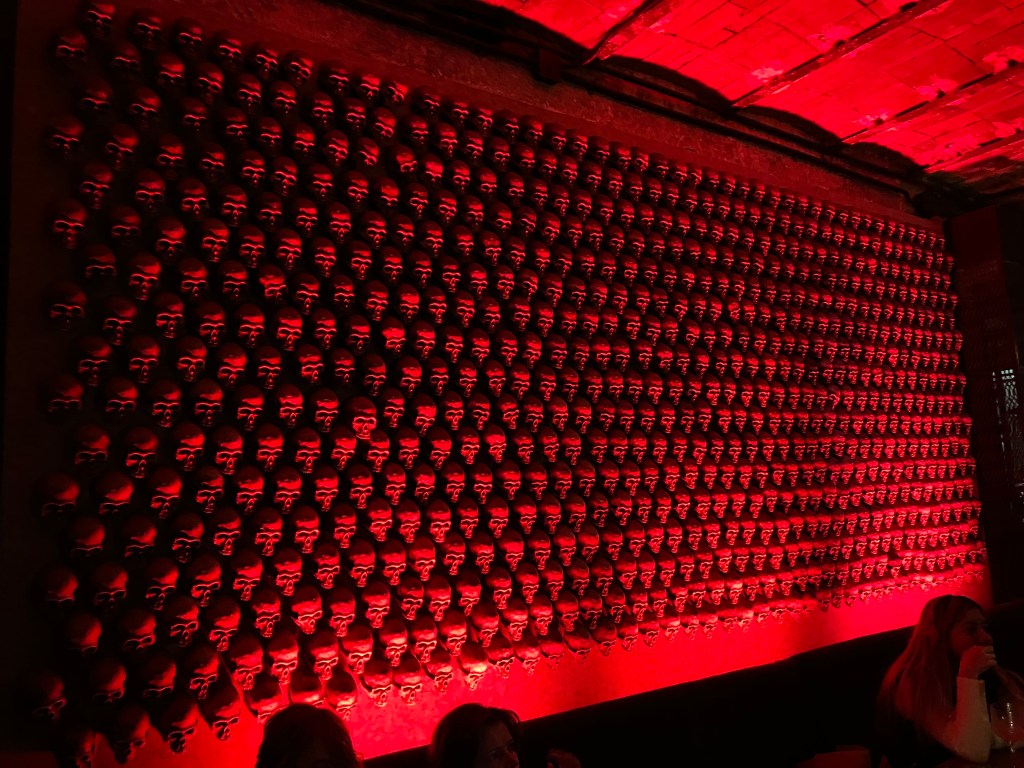

If Rock History is your thing, then a visit to The Crocodile, Seattle’s most famous music club, is a must. Originally opened in 1991, the music club at 2501 1st Avenue is legendary. In 2013, The Rolling Stone named it the seventh best music club in the US. VH1 named it the 7th most legendary rock club of all time. Kurt Cobain and Nirvana added to the club’s mystique by playing a secret show at the club on October 4th, 1992. In addition to music acts, the Crocodile also has a comedy club, movie theatre, and a hotel.

Iconic Edgewater Hotel where legends have slept and not slept at all

Not even a ten-minute walk down the hill from The Crocodile is the iconic Edgewater Hotel at the Seattle Wharf. Conde Nast Traveler named it as a top 10 hotel in the Pacific Northwest. The Seattle Times named it for having the best hotel view in Seattle. In 2024, Travel + Leisure named it the 2nd best hotel in Seattle. It’s the only Seattle hotel that is not only right on the Puget Sound — it’s right over it too! But its real claim to fame is the amazing rock acts that have stayed here. The Beatles, Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Elvis, Stevie Wonder, Blondie, David Bowie, The Monkees, Black Sabbath. Kurt Cobain, Pearl Jam, Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison, The Mamas and the Papas, Neil Young, and Rod Stewart. To name just a few! And I’m sure I’ve left out names. I love having a black coffee here at The Brim Coffee Shop and staring out at the shimmering Puget Sound, framed by the Olympics. I’ve also enjoyed some delicious meals at the Six Seven Restaurant and their happy hour, too.

Restaurants, cafes, and bars galore

Belltown has a wealth of restaurants, cafes, and bars, covering a smorgasbord of cuisines. One of my favorite restaurants in Seattle is the cozy, captivating Tilikum Place Café, where I had one of the best egg benedicts I’ve ever had. At Afro-Latin restaurant Lenox, my family celebrated three birthdays and shared dishes with a cacophony of tastes. At the stylish Kalabaw Bar and Kitchen, I love their Southeast Asia offerings, from lumpiang rolls from the Philippines, larb isaarn salad from Laos, and soft shell crab dried curry from Thailand. As I lived in Southeast Asia for over twenty years, I was happy that they got the tastes and heat level right.

For breakfast, I can’t resist Biscuit Bitch. Better to eat here on a pleasant day, though, as seating is all outdoors. The biscuit sandwiches, called Bitchwiches, have sausage, egg, and cheese and are irresistibly indulgent.

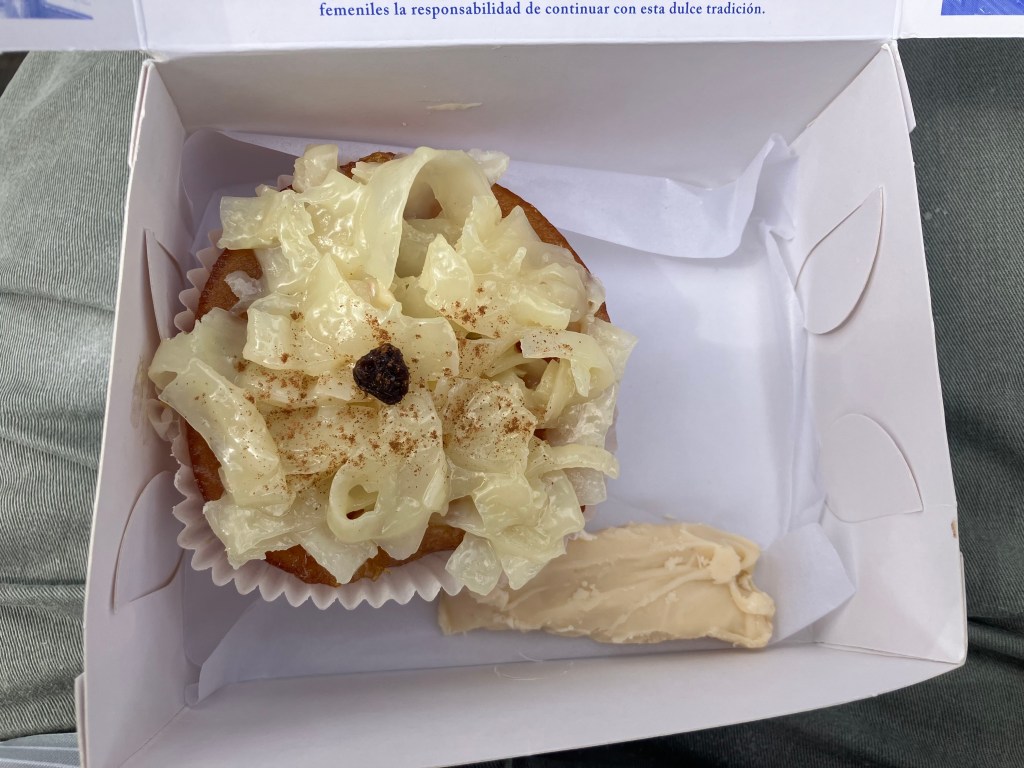

Cafes that I especially like are La Parisienne French Bakery, with what I believe are the best French pastries in Seattle. They’re phenomenally good. Bang Bang Café has a great, chilled vibe with solid, filling dishes. I love the vibe and space at Uptown Espresso Cafe. Coffee Tab’s mission, in addition to being a chilled place for a coffee, is to “help underserved youth achieve a higher quality of life.” On their website, they describe themselves as “Coffee Tab: where a coffee shop becomes a tabernacle.” Not sure exactly what that means, but it sounds noble. You can sip for a cause here.

For bars, Roquette, Some Random Bar, and Provisions are some great places for a beer (my usual drink) or a cocktail.

From morning to night, happiness is exploring the food and drink offerings in what is one of Seattle’s best culinary destinations.

Shop at shops and galleries you don’t see elsewhere

Belltown shopping takes you from the quirky to the serendipitous and surprising. For the widest variety of spices and herbs I’ve ever seen outside of the Spice Bazaar in Istanbul, stop by Mountain Rose Herbs Mercantile. Patagonia has a store where you can buy their high-quality clothing for the chilly Pacific Northwest winters — and tinned fish too. Ghost Vintage has funky, unexpected offerings. Juniors not only has great quirky offerings of vintage items and gifts (check out their cocktail napkins!), they also host the OBAMA (Official Bad Art Museum of Art).

For art galleries, Base Camp Galleries, Slip Gallery, Gallery Mack, Steinbrueck Native Gallery are worth browsing for art to enlighten or to simply lighten your living space.

Museums where you awe and guffaw

One of the most awe-inspiring museum spaces in Seattle is the Olympic Sculpture Park, a nine-acre free-admission park displaying massive sculptures from the Seattle Art Museum collection. Some of the world’s greatest sculptors have art displayed here: Alexander Calder, Richard Serra, Louise Bourgeois, and Claes Oldenburg. With a view of the Puget Sound and the Olympics, it is one of the most magnificent fusions of art and nature in a cityscape in the US.

On the other side of the equation is the irreverent and decidedly tacky (in a good way) Official Bad Art Museum of Art (OBAMA), which is at Juniors Vintage in Belltown.

Murals give Belltown a bright look, even on cloudy days

In a city known for its cloudy days, there’s nothing like a mural to provide a bright spark of light, inspiration, and introspection. Just turn a corner, and suddenly, a once-barren building wall is filled with a mural. There’s even an empty lot with cardboard cut-outs of human figures. Not sure what they mean. But that’s the charm of Belltown. Always a surprise.

Belltown connects you to the rest of Seattle, too — on foot and by bike

With the Elliott Bay Connections (EBC) project, backed by Melinda French Gates and Mackenzie Scott, defunct street rail lines have been replaced with a bike and foot path that connects a new waterfront park with the Olympic Sculpture Park and Myrtle Edwards Park. A stroll on this path gives you a spectacular view of the light dancing off the water of the Puget Sound and the majesty of the distant Olympics as you pass through Belltown on your way to the revitalized waterfront. By now, the magic of Seattle and its coolest neighborhood has revitalized you, too.