-

If You Have One Night in Bangkok

Since my first visit to Bangkok in 1981, I’ve been back dozens of times. For a few years I even commuted to a job that was based here. I’ve seen the city transform again and again from a seedy backwater with a “reputation” to a glittering, glamorous metropolis with some gritty corners. But there’s one label that no one has ever put on Bangkok and that is boring.

So imagine the challenge I set for myself on my last trip: if I only had one night in the city what would I do?

For inspiration I used the lyrics from the Murray Head song, One Night in Bangkok:

One night in Bangkok makes a hard man humble

Not much between despair and ecstasy

One night in Bangkok and the tough guys tumble

Can’t be too careful with your company

I can feel the Devil walking next to me

With those alarmist lyrics I decided I needed a really good meal to fuel the long evening ahead.

SPOILED BY BANGKOK’S BEST STEAKHOUSE

For fortification I started with a perfectly executed Citrus Martini, shaken not stirred, at the lushly appointed “Manhattan Lounge” at the JW Marriott Hotel. I followed this with dinner at the “New York Steakhouse” next door, consistently rated as Bangkok’s best. That’s a tough accolade to get year after year in a food-centered city like this. I couldn’t help but compare the experience here with a famous steakhouse in Palm Springs, California earlier this year where a grumpy, BMI-challenged waiter gave my family and I a Tomahawk-steak on a large platter where we all tucked in forks and sharp knives at the ready. The “New York Steakhouse’s” version of the Tomahawk-steak was altogether a different, much more elevated experience. When the waitresses with model-like looks and killer smiles draped the elegantly cut slices of meat on the Tomahawk bone I knew it was going to be tough to dine at an American steakhouse again. I’ve now been spoiled.

ASIA’S MOST HAPPENING STREET

Properly nourished, I headed out with a friend to explore nearby Soi 11, in my opinion Asia’s most happening street. When you think of nightlife areas in Asia, Hong Kong’s raucous Lan Kwai Fong springs to mind, or its more trendy, edgier sister Soho, or the upscale Xintiandi district in Shanghai or Singapore’s tony Club Street or Seoul’s fashionista Gangham district. But whereas those other nightlife areas

give you a non-representative slice of those cities’ lives, on Soi 11 you feel the entire human spectrum and kinetic energy of the city, Bangkok on full display and in your face.

Soi 11 is where I was going to spend my one night in Bangkok.

Our journey up and down and from ground-level to high above the Soi was a both a trek across broken sidewalk pavements and a peek into the aspirations of the people there that make the Soi a place of unyielding buzz. From “Cheap Charlie’s” with its outside pavement seating and a reputation for the cheapest beers in Bangkok to “Above 11” for a contemplative view of the city that looks a lot tamer 33 floors up, away from the stumbling crowds and the cruising pink and yellow and green taxis that always seem to barely miss hitting someone. The skyline’s supercharged sparkle was borderline surreal. Emerald City on steroids.

PEOPLE-WATCHING PERCH

We found a central perch at “Oskar’s”, which gave us a panorama view of the Soi in action. With a counter seat, you can see the denizens of the street marching purposely towards a destination or lurching from one bar to the next. Usually packed after 9pm, it becomes the Soi’s defacto people watching fulcrum: inside the bar everyone is rubbing elbows with everyone else, in a hurry to meet or make friends. It is not a place for a solitary drink. Or soulful chats for that matter. Meaningful encounters just isn’t on the menu in this place.

Having a tough time hearing each other, my friend and I made our way to the quieter “Wolff’s”, owned by former private investigator Malcolm Schaverien who writes thriller novels under the pseudonym of Harlan Wolff. Mr. Schaverien provided a bit of oral history of the Soi and its rise up Bangkok’s neon rankings: “Soi 11 became the local…nightspot when Q Bar first offered the option of trendy nightlife for those living on Sukhumvit. Before that we had pubs, gogo bars, cocktail lounges, restaurants and hotel bars – that was about it. So we would mostly make the trek to Silom or Siam Square for nightlife. After Q Bar came Bed Supper Club and others making Soi 11 a ‘trendy’ destination.”

Sadly, both Bed Supper Club and Q Bar are now closed. A hotel is now being built where Bed Supper Club was. Q Bar is being transformed in a new venue called The District. The Soi’s reinvention continues.

When I asked Mr. Schaverien why he created “Wolff’s” he said: “I was nostalgic for the classic bar I remember from my early days. The sort of place where people meet and talk over cocktails or a glass of wine. I couldn’t find one in my area so I built one with bricks and a copper top bar.”

A few steps away we visited Brew, for a stylish beer-focused experience. Owner Chris Foo said the bar was “based on a space under a Trappist…Monastery in the mountains where monks produced beer. The water coming down the mountain would

be collected and used to make the Trappist Beers and then they would store the beer

in oak casks for fermentation.” With “the largest selection of beers and ciders in Asia,” Mr. Foo’s aims to make his bar a destination for beer-lovers. The menu was amazingly long. I could imagine drinking a different beer there almost every day of the year. Not a bad goal to set yourself.

MUSIC YOU DON’T USUALLY GET ELSEWHERE

At some point in any long evening music is as good a reason as any other to visit a bar. And Soi 11 is one of the best destinations in Bangkok for the more unusual types of music. At “Apotheka”, blues is played every evening except Sunday, when it’s jazz. With its dark wood interior the bar could be in Chicago or New York, only it isn’t. It’s completely open in the tropical heat and we briefly lingered on the sidewalk before being sucked into the bar for a better view of the band leader playing the trombone with aplomb while coaxing his fellow musicians. Munching on popcorn while sipping a craft beer was a great way to pass the time.

Above “Apotheka” is yet another refuge from the Soi, “Nest”, where we sought temporary solace. With plants and alcoves and a floor covered in sand in places to reinforce the you’re-in-the-tropics feel, a guitarist provided the music to make it a chill place to hang.

SINGLE-DIGIT TIME

There comes a point in any evening where the drinks start to hit the double-digit point and the hour hand single digits. That’s when noisier, more primal venues hold greater appeal. “Levels”, on the 9th floor of the Aloft Hotel, fit that bill. It too had a view, of Soi 11 as it marched through the chaotic tide of humanity to not-so-distant Sukhumvit. With a more aggressive but more snappily dressed crowd, it was an ideal place to see the Soi from a different vantage point. It has a gigantic curving bar with a colossal sparkling chandelier above it, like a fountain of descending glass that never quite splashes down.

After a drink there I too started my transformation into one of the lurching zombies of the late night Soi. Not quite an extra from the movie World War Z but in a few more hours I might have passed for one. I walked past brightly-lit drink and food carts that lined the streets selling pad thai, seafood of all kinds packed in ice, stacks of coconuts. There was even a shiny yellow van with seats out front called Taco Taxi. I thought of some more lyrics from Murray Head’s song:

“One night in Bangkok and the world’s your oyster.

The bars are temples but the pearls ain’t free.”

ONE NIGHT ISN’T ENOUGH

The Soi has startling variety of venues: from an Indian nightclub called “Daawat” in the Ambassador Hotel, to a German bar called “Old German Beerhouse”, from an Italian pizzeria called “Limoncello” to a bar called “The Alchemist” tucked away on an alcove just off the main Soi, to a wine bar called “Zaks” to a Thai restaurant, “Suk 11”, set in a traditional wooden building. That doesn’t begin to describe the diversity of choices on the Soi. One night in Bangkok isn’t enough to explore this street.

I landed with a delightful thud in a basement after hours club named “Climax.” Given the way I was feeling, the long night clearly tugging on me, it certainly wasn’t the climax of my evening but with a glazed view of the revelers it seemed to have lived up to its name for some people.

No night in Bangkok is complete unless you have a place to R & R (rest and recover) afterwards. The nearby JW Marriott certainly provided that for me. In the morning, I sweated out the previous evening’s indulgences with a lengthy session in the steambath and sauna at the hotel’s state-of-the-art spa. With a swim afterwards I was practically as good as new.

Relaxing on a lounge chair by the soothing aquamarine pool, I considered with a clear head the challenge I had set for myself. What was I thinking? Who wants to spend just one night in Bangkok?

Published in Asian Journeys magazine, December 2015-January 2016

-

Under Tibet’s Breathtaking Cobalt Sky

The highest point of my trip to Tibet is the Kharola glacier on the road from Lhasa to the province’s second largest city, Shigatse. At 5,500 meters, the air is thin – a short jog winding me – but the scenery rich. Poles topped by yak hair and wrapped with flapping prayer flags flank a simple white stupa that has as its backdrop the glacier draped over a craggy mountain while outlined by a sky of such an extraordinary cobalt blue that you want to lick it. Literally.

OUT OF THIS WORLD YET WITHIN IN

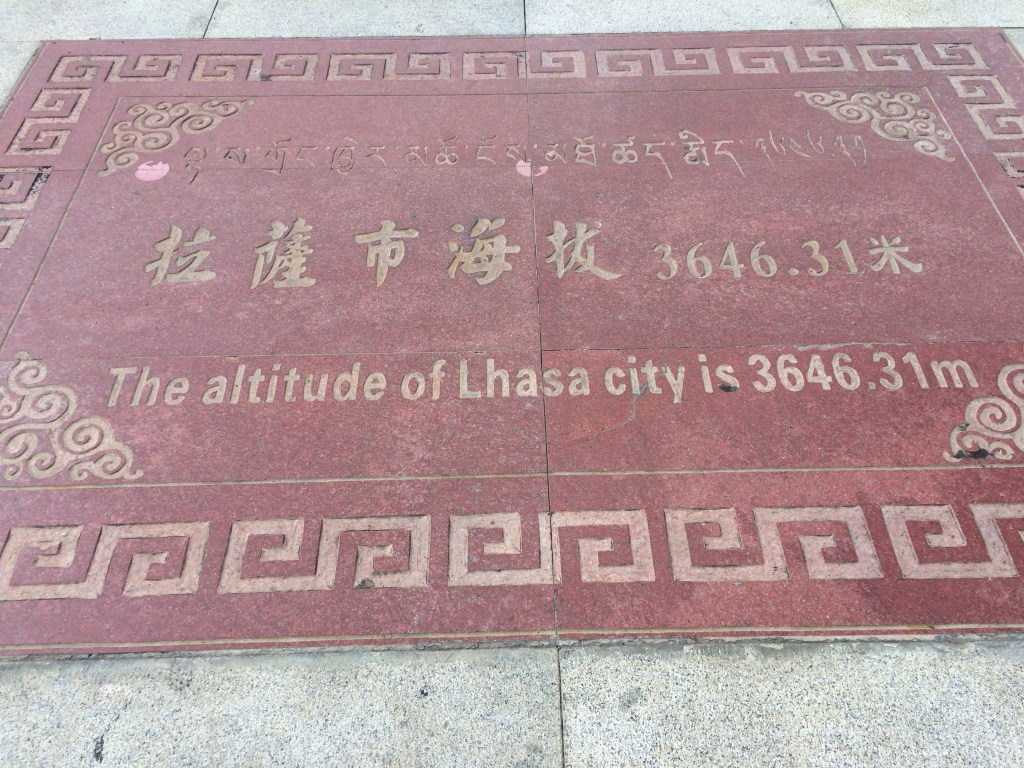

Tibet is a place that feels out-of-kilter both with the country it sits within as well as the earth it sits upon. The flight to Tibet teases you as it soars over the Himalayas, icy peaks defiantly punching through cloud cover while far below remote, deserted roads struggle to find a path in the barren plateau. When the Air China flight lands in Lhasa, the disembodied voice on the intercom says to be careful of altitude sickness. At 3,656 meters that warning resonates with me.

THE ALTITUDE CAN BRING YOU DOWN

While I didn’t experience altitude sickness on trips to Bhutan, Nepal or the altiplano of Peru and Bolivia, I realized it is a risk. It seems to strike at whim. Diamox, a medication effective at preventing it, works for me. While I vowed to take it very easy on my first day, Lhasa’s kinetic energy and otherworldliness, pulls me forward. Fortified by a lunch at the atmospheric House of Shambala restaurant I walk more than 20,000 steps. I experience sunset on the rooftop of the Tibetan Family restaurant over a dinner of fried yak-filled momos. The diminishing light of day illuminates the nearby golden canopies of Johkang Temple. Upon my return to the Gang-Gyan hotel, people in the clinic off the hotel’s lobby suck on oxygen from tarnished tanks while a nurse with crossed arms stands nearby.

LHASA’S SPIRITUAL AND COMMERCIAL HEART

The spiritual and commercial heart of Lhasa is the Johkang Temple and the adjacent Barkhor Square, ten minutes stroll from my hotel through twisting, narrow alleyways. A hive of religious fervor, to get onto the square requires passing through a gauntlet of very tight security. Omnipresent cameras on rooftops and along the eaves of buildings watch everyone. The security checkpoints have metal detectors, X-ray machines and card readers that capture locals’ identity information. Elite SWAT squads control these checkpoints while scattered around the square small squads of police in full riot gear stand at the ready. Their presence provides an ominous sense of the Chinese government’s heavy hand and a recognition that the surface calm is perhaps superficial.

On Barkhor Square I follow the pilgrims’ circumambulation around the Johkang Temple, passing restaurants, tea houses offering Tibetan butter and sweet tea, shops selling prayer flags, beads and other religious items, and antiques of various authenticity. The effect is an ever-moving, ever changing kaleidoscope of people with different poses, emotions, hopes, prayers, despair, physical conditions, and triumphs of sorts moving like a human tide clockwise around the temple and wondering if their life’s lots might change en route – or ever. It’s as turbulent as a Tibetan sky. A scrum of people surrounds a one-legged pilgrim who slams metal bricks together before prostrating himself on the ground. Then he lifts himself up and repeats the process again a few steps further on. It’s easy to hook onto the devotees’ tide and get pulled into their mania. Maybe the thin air helped —oxygen deprivation giving a light-headed perspective on the scene, like lining up a shot through fisheye lens for a distorted view of the world.

MAGNETIC “HOUSE OF MYSTERIES”

King Songtsen Gampo started building the Johkang Temple in 652 to honor his Chinese and Nepalese wives. Known in ancient times as the House of Mysteries it was finished nearly a thousand years later in 1610 during the reign of the 5th Dalai Lama. Two giant incense burners in the front and rear of the temple help give Lhasa its distinctive aroma.

Just outside and within the temple the fervor approaches fever pitch, dozens of people prostrating themselves then lifting themselves up in hope before throwing themselves down again in repetitive demonstrations of piety. The crush inside is driven by the determination that their prayers be heard. Blessings by monks are seemingly cursory as they try to move the crowd through. I don’t understand what people are asking for but I do recognize hope as a universal need. The temple’s magnetism keeps me close to it and the square during my Lhasa visit. That evening I dine on grilled mushrooms and ginger carrot soup at the packed Makye Ame restaurant overlooking the rear of the temple. The yellow-painted building it is in was the 6th Dalai Lama’s palace and named after his mistress. He wrote a poem about her here.

ONE OF THE WORLD’S GREAT PALACES

About 1,000 meters away is the administrative heart of Tibetan Buddhism, Potala Palace, the residence of Dalai Lamas until the 1959 Chinese invasion ended the Tibetan uprising and forced the 14th Dalai Lama into exile. The 5th Daiai Lama started building it in 1645 on the remains of an earlier one from 637 by King Songtsen Gampo. Its location is strategic: between the influential Drepung and Sera monasteries, and Lhasa’s old city. It took three years to build and another forty-five before the interior’s completion in 1694.

It’s a massive edifice: 400 meters from east to west and 350 meters north to south with stone walls around 3 meters thick in most places and 5 meters thick at the base. It’s more than 117 meters high on top of Red Mountain and rises more than 300 meters above the Lhasa Valley floor. It has over 1,000 rooms and some 200,000 statues. The areas painted white are the administrative parts of the palace, while the red painted ones are where the Dalai Lamas resided and ruled. Assembly halls, shrines and thrones of the past Dalai Lamas are located here, including the cave where King Songtsen Gampo meditated. Gilt-covered roofs reflect the intermittent sparkling sunlight giving an unusual sense of lightness to such a sturdy structure. It was lightly damaged during the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s premier Chou En-Lai having protected it.

One of the world’s great palaces, perhaps France’s Versailles or Russia’s Winter Palace come close to matching its splendor. I pass through a number of security gauntlets before entering. At the palace’s base, flowers are in full bloom — Tibetan summer and spring converging into a single, very short season of vibrant colors in a landscape that is dour and forbidding most of the year. Potala Palace tickets are timed and visitors move quickly up the stairs in the thin air to meet the various deadlines. Unlike other museum-like grand palaces, it is a place of devotion. Tibetans prostrate themselves in front of shrines and religious relics. Security brusquely moves them along.

SPINNING PRAYER WHEELS TO WIN AT LIFE’S LOTTERY

The various Dalai Lama thrones give an indication of their personalities and styles of ruling. Many are modest elevated platforms to preside cross-legged over subjects. The 6th Dalai Lama was probably the most controversial because of his notorious lifestyle as a womanizer and magician. He has by far the largest throne. The second largest throne belongs to the current Dalai Lama. I also notice the size of his throne at Norbulingka Palace, known as the summer palace. His throne of gold with silver steps is the largest of the Dalai Lamas with residences there. After exiting Potala Palace down steep steps in the back I come to an endless line of prayer wheels which devotees spin — for luck or health — to help win in the lottery that is life. The sound of the spinning wheels rubbing against aging wood creates a humming that rises in the air to create another dimension of etherealness to the palace.

PROTECTION AGAINST NIGHTMARES

If the Potala Palace and Johkang Temple are the administrative and spiritual hearts of Tibet, Sera Monastery is the intellectual heart. Founded in 1419 the sprawling monastery sits at the foot of the mountains at Lhasa’s edge, a remote nunnery high on a hill above it. Parents take their children here to inoculate them against nightmares. After a monk’s blessing ashes are smeared on their noses and they walk away with smiling faces — safe in the knowledge that sleep will be just blissful dreams. In a sun-dappled courtyard nearby dozens of monks in pairs, one standing and one sitting, debate with vigor. The standing monks, fiddling with prayer beads and stamping their feet and clapping their hands, hurl Buddhist doctrine questions from the Five Major Texts at the sitting monks. The questions are theological ones with rhetorical twists and the gift of constructing eloquent responses prove the intellectual rigor of the monks. Eventually, they switch places. This sparring is mesmerizing to watch, like mental martial arts. The voices rising in challenging tones create a strangely melodious sound like binaural beats from a Haight-Ashbury hippy store. During the 1959 revolt, hundreds of monks were killed here and survivors set up a parallel monastery in exile in Sera, India.

BREATHTAKING’S DOUBLE MEANING

The Lhasa to Shigatse road gives an indication of Tibet’s magical landscape and breathtaking vastness. Just outside Lhasa a tunnel reveals the Yellow River, one of China’s and the world’s longest, beginning an over 5,000 kilometer journey to the sea. As the van climbs switchbacks, proud owners display regal Tibetan Mastiffs at scenic turnoffs and charge 10 yuan to have a photo taken of them. The Khamba La pass at an elevation of 4,998 meters overlooks Yamdrok lake. The scimitar-shaped lake has a turquoise colour transforming chameleon-like in front of you as if reflective of volatile moods. Such a sacred sight at such an elevation brings a double meaning to the word breathtaking. It’s forbidden to eat the abundant fish from its crystalline, holy waters. At the shore Tibetans charge for sitting on decorated yaks with stoic demeanors.

In a few hours, past the Kharola glacier, is the city of Gyantse. The Dzong, fortress, lords over the city. I visit the Penchor Chode monastery, guarded by red, parapet-topped walls. The monastery’s main building, built between 1418 to 1425, is closed that day as the monks are engaged in a secret chanting ceremony. Having watched burly monks from the Yellow Hat sect chant at Ramoche temple in Lhasa I can imagine the intense, rumbling sound as the prayers emerge deep from their chests.

WHERE THE BRITISH INVADED TIBET

The Kumbum, a type of pagoda, next door was founded in 1497 by a Gyantse prince. It has nine levels, 108 gates and rises 35 meters. It has 76 chapels and is filled with entrancing Buddhist religious paintings that remind me of the legendary Mogao caves in Dunhuang. The Gyantse Kumbum is the most famous in Tibetan Buddhism. I climb ladders to reach the highest level, heavily lidded, all-seeing eyes painted at the top. The fortified red walls of the monastery seem to reach out finger-like to the forbidding heights of the nearby Dzong that protects it. The Dzong was the site in 1903 of a fierce battle between Tibet’s best troops and a colonial British invasion force known as the Younghusband expedition after Colonel Francis Younghusband. The battle was overseen by Brigadier General James Macdonald under the auspices of the Tibet Frontier Commission. Sent by the Viceroy of India Lord Curzon, the invasion was part of the 19th century “Great Game” between Great Britain and Russia for influence in Central Asia. Great Britain preemptively invaded Tibet to keep it out of Russia’s hands. After Gyantse fell, the British went on to seize Lhasa and dictate the terms of the 1904 Treaty of Lhasa where the Chinese government agreed to not let any other country interfere in Tibet.

PANCHEN LAMA’S HOME

After a night at the garishly decorated Gesar Hotel in Shigatse, I visit the Tashi Lhunpo Monastery. Founded in 1447 by the 1st Dalai Lama, this is the home of the Panchen Lamas, Tibetan Buddhism’s second highest rank. The current Panchen Lama is only 28 years old. The Gorkha Kingdom sacked the monastery when they invaded in 1791 but they were quickly pushed out by a combined Tibetan and Chinese army. It was also damaged during the Cultural Revolution. The monastery climbs up the mountain and is protected by a nearby Dzong. Inside there is a vast assembly hall, now empty, that I can imagine being filled with chanting monks sitting cross-legged. At a temple, the guide points out what looks like a gold-covered statue of the previous Panchen Lama with a yak hair wig and a golden bell in his uplifted hand. Only it isn’t a statue but the mummified body of the lama, deceased since 1989.

The train back to Lhasa follows the Yarlung Tsapo River Valley. When the river leaves the Tibetan Plateau, it carves a canyon deeper and longer than the Grand Canyon — one of the world’s great sights few people get to see.

FROM SUMMER SUN TO STORMY SKIES

On my last night, I join a couple at Po Ba Tsang restaurant, featuring Tibetan dancing. The dancing strikes me as something from one of the Central Asian stans — aggressive leg thumps creating mini earth tremors on the wooden floor. Dinner is momos floating in a broth with fried yak cheese on the side. Crisp Lhasa beer helps down it.

That night I see Potala Palace perched high above the vast Potala Square on the opposite side of Beijing Middle Road. Potala Square has dancing musical fountains, a billboard featuring past and present Chinese leaders and the angular Tibet Peaceful Liberation monument guarded by soldiers. Lit against the blackest of nights, thick clouds obscuring stars, Potala Palace is revelatory, apparition-like. While my Tibet visit is in the midst of the summer rainy season I experience warm, mostly sunny days during my stay. It is ironic then that on my walk back to the hotel a nightmarish thunder and lightning storm sky splits the sky and spits hail. I wish that a Sera Monastery monk had put some nightmare inoculating ash on my nose too.

A few weeks later during an Uber ride to New York’s LaGuardia airport, I ask the driver where he is from. “Tibet,” he says. I tell him what a coincidence that I got him for my driver as I had recently been there. He smiles at me in the rearview mirror and says, “Karma.”

TRAVEL TIPS:

Restaurants:

-Tibetan Family Kitchen

-Makye Ame Tibetan restaurant

-Po Ba Tsang restaurant

-House of Shambala restaurant

Hotels:

-The Gang-Gyan Hotel in Lhasa’s old city has quirky touches: a humidifier that looks like a character from an animated cartoon and motion sensor activated hallway lights that provide light where you are and pitch darkness everywhere else.

-The Gesar Hotel in Shigatse is garishly decorated like a Disney-fied version of yurt fit for a khan.

Tibetan Travel Permit:

A China visa gets you into the country, but not Tibet. You’re not allowed to travel alone or even visit a temple without an official guide. A tour company can get you a Tibet Travel Permit. Mine is checked four times before I enter Tibet. It has a holographic-like stamp stapled to a paper with my details.

Altitude Sickness:

Consider how to prevent altitude sickness before your trip. Diamox, a well-known medication, works. The supplement Ginkgo Biloba supposedly helps. Going to a high elevation in phases allows the body to adjust. I stay two nights in Chengdu at 1,640 meters before travelling to Lhasa. My uncle, a doctor with high altitude climbing experience, notes that going straight from sea-level to Tibet will almost certainly get you sick.

Photography:

In Lhasa, photography isn’t allowed at the temples and monasteries. Outside Lhasa it is allowed but sometimes at a very high cost. At Shigatse’s Tashi Lhunpo monastery, some of the temples requested a 150 RMB photography fee.

Getting there:

Flights to Lhasa leave from a number of Chinese cities. My round trip airfare on Air China from Chengdu during the peak summer season is a pricey US$577. The flight is 2 hours.

Published in Asian Journeys magazine, October-November 2018

-

Kamikazes ‘R’ Us: In Japan, A Peace Museum Celebrates Suicidal Warriors

Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots After the September 11th hijackers carried out their evil deeds across America, the media and just about everyone else were left scratching their heads wondering what sickness could possibly drive young men to choose suicide as a way to prove their allegiance to an ideology. The same bafflement applies to the Tamil Tiger bombers blowing up politicians and themselves while conducting their war against the Sri Lankan government. And, of course, to the crazy legions of Palestinian terrorists turning themselves into human bombs at Tel Aviv discos or Jerusalem pizza parlors.

While I doubt we’ll ever fully understand the private motivation or personal confusion of the individual bombers, today’s suicides aren’t the first: they are all following in the doomed footsteps of the Japanese kamikaze pilots of World War II. Bizarrely enough, for those who interested to learn more about these infamous pilots and their mystique, there is a “Peace Museum” honoring kamikazes in the very peaceful village of Chiran.

Chiran is a beautiful little town an hour’s drive south of Kagoshima on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu. Terraced rice paddies and forested hills greet a traveler’s arrival in what is a gem of rural Japan. A narrow goldfish pond runs alongside one of the sidewalks that ribbons through the center of the town. Small shops sell purple yam chips glazed in sugar, a regional specialty. They even sell yam ice cream. Near the center of town are samurai houses from the 19th century. Tranquil gardens, hidden from the road by a high and lengthy stone wall, lounge behind each of the houses. Tourists drift in and out as they savor the delightful mixing of elements necessary for a Japanese garden – color and sound, texture and moisture. It is easy to imagine how the “perfect retreat for the spirit” can be achieved in some of these gardens, which are protected national monuments.

Those gardens and their past warrior occupants epitomize the dueling essence of the town. For the samurai citizens of the past surely were the inspiration for the kamikaze warriors of World War II. At the Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots, the heroic lives – and dramatic deaths – of the samurais are honored in great detail.

Chiran was the choice for the kamikaze museum because one of the airfields for the “special attack corps” (no kidding, that was their official military identification) was in the town’s vicinity. Their eerie motto was “a battleship for every aircraft,” and if they didn’t succeed in their mission there was no worry about military punishment because they all died trying.

Recovered Mitsubishi Zero The museum was opened in 1975 as part of a complex. Next to it is the Heiwa-Kannon Temple containing the goddess Kannon, who appropriately enough in this case is symbolic of pity. The temple was opened in 1955. The museum is in the shape of a plane. In front of it is a bronze statue of a kamikaze pilot next to a Mitsubishi Zero. In the entrance hall is a huge lacquer-wood painting of a kamikaze pilot’s body being lifted from a burning plane and gently carried by a half-dozen angelic spirits to a better afterworld – his sacrifice supposedly not in vain.

On the day I dropped by for a visit, the museum was jam-packed with visitors. That surprised me a bit because I had visited a number of museums in Kagoshima and its vicinity and all of them were noticeably empty. Not this one. Perhaps interest and shock over the September 11th attack made the museum a more interesting and timely destination for Japanese trying to find historical references for a new crisis.

Statues of pilots saluting Mitsubishi Zero The museum’s main hall is dominated by a Mitsubishi Zero and a statue of a brave pilot saluting from the cockpit. His proud, stiff-armed salute is being returned by two other pilots bidding him farewell – from the base and no doubt from his life too. Surrounding the plane are exhibits featuring personal mementos from the actual pilots themselves: letters, watches, binoculars and photos, for example. In all of the snapshots, the would-be suicide bombers are smiling, arm-wresting, saluting, eating, drinking ceremonial cups of sake, and being waved off to duty by cooing girls with flowers in their hands.

The visual presentation is only the beginning. The voice on the audio guide describes all of the pilots’ love of life, adding the discreet caveat that their willingness to pay the supreme price is the result of a patriotic virtue to defend the homeland. The audio guide’s narrator, with her unusually sweet voice, describes how the pilots would cry into their pillows on the night before their missions, leaving the pillows soaking wet with tears. But seconds later she goes on to describe the kamikazes’ brave smiles as they flew off as just that – brave smiles. No comment is made about the opposing realities of suicide and bravery.

Kamikaze pilots entered World War II during the battle for Okinawa. In total, 1,036 pilots sacrificed themselves in explosives-filled planes in a desperate effort to try and stop the American invasion. Of course, the tactic and the kamikazes failed. In addition to Chiran, they flew from bases in Bansei, Miyakonojo, Kengun and Taiwan.

In the museum there was a video of the Battle of Okinawa. The benches in front of the video were full of people staring somberly as plane after plane was shown being destroyed by U.S. artillery before hitting a targeted battleship. Eventually, one kamikaze Zero did hit a ship, but the senseless loss comes through clearly in the video. At the moment of impact, the soundtrack changes from the battle sounds of exploding flak and fiery descents of planes to classical music – as if the whole situation were all a bad dream.

Painting in Chiran Peace Museum for Kamikaze Pilots Outside of the museum’s theater, there is a room filled with uniforms. And another room with colorful funeral wreaths piled high on the walls. And still another with a crashed plane that had been recovered, cleaned up and put on display, minus half the fuselage. But it is outside the museum next to the Kannon Temple where a visitor gets the closest sense of the men in the photos: Rows of stone lanterns cover the grounds. On each one there is a relief carving of a kamikaze pilot with a small Mona Lisa smile on his face. Their enigmatic smiles direct you to the lone surviving barracks where some of the pilots spent their last night.

Stone lanterns honoring kamikaze pilots Decades after they were built, the kamikaze barracks remain just as they were when they housed their terminal residents: very spartan, and camouflaged by trees to protect them from American bombers. Naked light bulbs throw a harsh glare on the room, and lumpy futons covered with green blankets sit on raised wooden platforms. But it was those pillows that drew my attention, the pillows that supposedly were saturated with tears on the morning of the suicide pilots’ last day. It was on those pillows that the kamikazes left their fears and their futures behind to do their awful work.

Kamikaze pilots’ barracks Published in The Asian Wall Street Journal, November 16, 2001

-

The Price of Peace: Where the Last Global War Ended

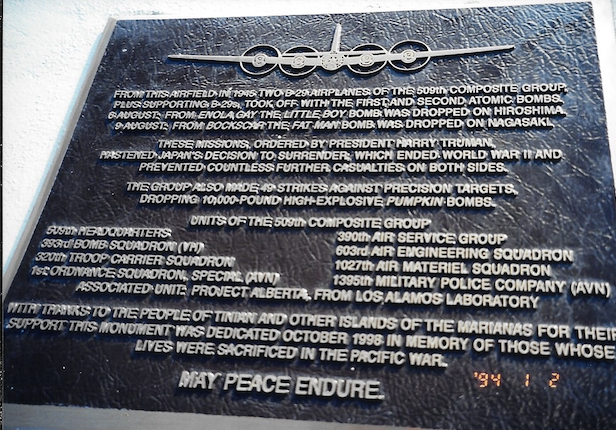

Tinian runway where Enola Gay and Bockscar took off on their missions As the free world hunkers down for the first global war of the 21st century it’s worth taking a glimpse at a place where the last global war ended: at Tinian Island, where the planes that dropped the atom bombs on Japan took off. My family recently took a trip to Tinian, a Manhattan-shaped island in the Mariana Islands where the Manhattan project neared its end. Colonel Paul Tibbets, piloting the B-29 Superfortress named Enola Gay, took off from here to drop the bomb, “Little Boy,” on Hiroshima. Three days later, Major Charles Sweeney, also took off from here in the airplane named Bockscar to drop the bomb on Nagasaki.

Atomic pit No. 1 where Hiroshima bomb was loaded At the end of World War II Tinian was the busiest airfield on earth, with six gigantic runways. Nineteen-thousand combat missions flew from here. Now it’s a quiet place with some unusual attractions. With a population of less than 3,000 people in an area of 39 square miles, it lies next to Saipan in the Mariana Islands and is politically part of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, a U.S. territory.

Atomic pit No. 2 where Nagasaki bomb was loaded When we got off the boat from Saipan, my family’s first stop was the casino that today is the island’s largest business. Tinian Dynasty Hotel and Casino is a flash place — a Macau-style casino occupying a piece of South Seas paradise. But unlike other hotels in the tropics, it doesn’t leverage its location. No al-fresco dining to pull you away from the gaming tables. The windows in the rooms don’t open to let in the warm breezes. After all, you might be tempted to enjoy the tropical weather outside — leaving the pleasures of the slot machines behind.

Plaque to commemorate that planes with atomic bombs left from this airfield

Sign to where atomic bombs were loaded We started our touring by driving to the Suicide Cliffs on the south side of the island. As American troops were invading the island at the end of July 1944, Japanese civilians chose suicide rather than surrender. They jumped to their deaths from here. Their fanatical behavior has an eery parallel with the terrorists of today. The site is spectacular and empty with vertical cliffs dropping to crashing waves and a sea of startling blue. We were the only visitors, deepening the natural solitude of the area and making it feel as if we really were in a sacred place.

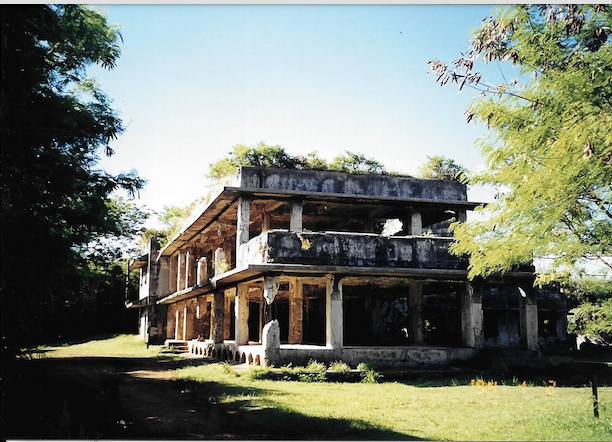

Jungle encroaching on Tinian road From there we drove clear across the island. Because Tinian is shaped like Manhattan the military named the island’s roads after streets in New York. Broadway is a long straight avenue, but unlike its famous namesake there is no traffic at all, no pedestrians, and only a few gutted buildings from World War II days. Weeds sprouted from the asphalt. Jungle is starting to creep in at the edges.

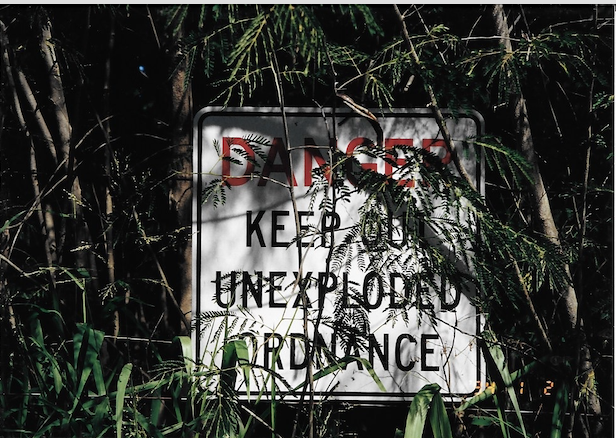

Unexploded World War II ordnance on Tinian At a roundabout there was a ruined Japanese shrine. We drove around it to a truly forbidding part of the island. The road narrowed and every couple of yards there were signs on jungle-covered barbed-wire fences that warned of explosive ordinance. After a couple of miles there was a dirt turnoff to the left where we stopped next to a large grave-size plot with a few flowers on it and a headless palm-tree in front of it. A wooden sign read, “Atomic Bomb Pit No. 1.” The plaque described how the bomb dropped on Hiroshima was winched into the belly of the Enola Gay at this spot.

Ruins of World War II barracks About 50 feet away was another signpost: “Atomic Bomb Pit No. 2.” Another atom bomb, “Fat Man,” was winched into the belly of Bock’s Car here prior to its journey to Nagasaki.

I’ve visited the Los Alamos laboratories in New Mexico, where the U.S. atomic bomb project feverishly was pursued, and its museum. I’ve also visited the museums at Hiroshima and Nagasaki and saw the horrors that befell the victims of the bombs. But this site at Tinian affected me the most: the silence; the complete absence of tourists or any other people; the sense of decay as if we were standing in a post-nuclear war world, one decimated by atomic weapons.

Abandoned World War II tanks Further on we discovered the runways, monumental ribbons of concrete, now silent and slowly being reclaimed by the lush vegetation of the surrounding jungle. Near some Japanese bunkers on the side of one runway were plaques honoring the U.S. military units that served here. Then we found ourselves driving down the very straight 8th Avenue towards the hotel. We passed the sign for the 509th Bomber Group and its slogan bragging that it was the first to use atomic weapons. This was Col. Tibbets’s unit.

Tinian as seen from Saipan ferry With some relief we reached the town again. We visited the ruins of a previous civilization: a collection of huge latte stones — like a South Pacific Stonehenge — that were the foundations of a home belonging to a legendary Chamorro chieftain, Taga the Great. Within moments we were back at the familiar surroundings of the casino. Other than the gambling and eating the only other entertainment at the hotel was a troupe of Russian dancers. But as I sat down to watch them gamely doing their routine I realized that I was the only one in the audience. It was an empty house.

Foundations of home belonging to Chamorro chieftain Taga the Great Published in The Wall Street Journal, March 1, 2002

-

Bandung: the Heart of Java

A journey to Bandung allows you to traverse the past, present and even future of Indonesia all in one city. The capital of West Java and Indonesia’s fourth largest city with 2.6 million people, you can see everything from the colonial to the kitsch. And it’s only 180 kilometers from Jakarta. With the new highway cutting travel time from five hours to two, it’s an easy day trip.

First, the past. Bandung was established in the late 19th century by the Dutch as a garrison town. In 1920 they opened the Bandung Institute of Technology, Indonesia’s top scientific university. Its luscious, sprawling campus has Indo-European architecture with pointy Minangkabau-style roofs on many of the buildings. On the Saturday that I was there, students were chilling on lawns, singing, playing guitars, dancing with drums —- even studying, using typewriters. Yes, typewriters. The founder of Indonesia, Soekarno, lived here from 1920-25.

Students at Bandung Institute of Technology At the outskirts of the city, at the Museum Geologi, a massive colonial building that used to house the Dutch Geological Service, are a number of stuffed animals, nature exhibits and fossils, the most famous of which is the skull of Pithecanthropus erectus, the prehistoric Java Man.

Dutch colonial-era architecture In the center of town at Jalan Braga, rundown Dutch colonial buildings form a shopping street with some great antique stores. The dust-coated stores give you a sense of Bandung’s multi-ethnic heritage with Javanese, Chinese, Dutch relics all competing for space and buyers.

Art deco buildings in Bandung But it’s the art-deco buildings nearby that define Bandung’s notable architectural footprint. From the Savoy Homman Hotel to the Grand Hotel Preanger to the Gedung Merdeka complex, Bandung is an art-deco museum. Frank Lloyd Wright would have appreciated the grey, almost Mayan angular touches that make Jalan Asia-Afrika unique among major boulevards in Asia. Think a tropical version of lower Fifth Avenue in Manhattan.

Art deco building in Bandung At the Gedung Merdeka Bandung reached the height of its fame. In 1955, Soekarno, Chou En-Lai, Nasser, Ho Chi Minh and other third world leaders met at the AfroAsian Conference, otherwise known as the Bandung Conference. The building, dating from 1879, was known as the “Concordia Sociteit”, the meeting hall of Dutch colonial associations. In April 1955, it was literally the capital of the third world. The Bandung Conference’s 10 principles defined the Non-Aligned Movement throughout the coming Cold War period until the collapse of the Soviet Union. Some of those principles, such as non-aggression, respect for sovereignty, non-interference in internal affairs, and peaceful co-existence are as timely today as they were then. The conference lit the fire of a number of anti-colonial movements that followed in the coming decade. The massive hall where the delegates met is filled with flags of the 29 participating nations. In the museum you can learn about what happened here and see wax figures of some of the most famous leaders who attended, including Soekarno, speaking from a podium.

Wolverine statue on Jeans Street Now, the present. You should have lunch at a Sundanese restaurant at the hillside suburb of Dago, where elegant mansions populate lush tree-covered roads. Nearby is Jeans Street, Jalan Cihampelas, where Bandung today defines itself. On the Saturday I was there, it was packed with cars, tour buses and shoppers. In front of its denim shops were massive statues of superheroes: from Superman to Spiderman to Wolverine from X-men. Buskers serenaded the crowd. Kitsch is cool here.

So what of Bandung in the future. With that new highway, it’s a favourite weekend destination for people from Jakarta. Whether it’s buying jeans, eating Sundanese food or breathing cool mountain air — at more than 700 meters the air is better here than Jakarta — it’s a great getaway. And with the Bandung Institute of Technology having produced great Indonesian leaders in the past, you can bet those of the future will come from here as well.

Published in South China Morning Post, June 17, 2009

-

Vietnam: Producing Smiles the Local Way at Suoi Tien Theme Park

Suoi Tien Theme Park We have heard the news about Hong Kong Disneyland’s missteps in trying to connect with its Chinese target audience. To have shark’s fin or not on its menu? Trying to get the park Feng Shui right. Alledgedly, rude staff. First, too few visitors. Then, over Chinese New Year too many. To the point where they had to lock the gates to hundreds of ticket holding visitors. Photos showed tourists scaling Disneyland’s fences to get inside. The managing director of Hong Kong Disneyland, Bill Ernest, apologized to the people of Hong Kong and China. “We are still learning in this market,” he said. “This is our very first Chinese New Year, frankly.” Hong Kong Chief Executive Donald Tsang said, “We feel disconsolate, but we have learnt a lesson.” Legislators in the territory feel the incident has damaged Hong Kong’s international image.

Yet, in Asia, there are very successful local theme parks who connect culturally with their target audience and produce smiles instead of headlines.

One such theme park is Suoi Tien, outside of Saigon. Its attractions are decidedly un-Disney in their make-up but their appeal is unmistakable.

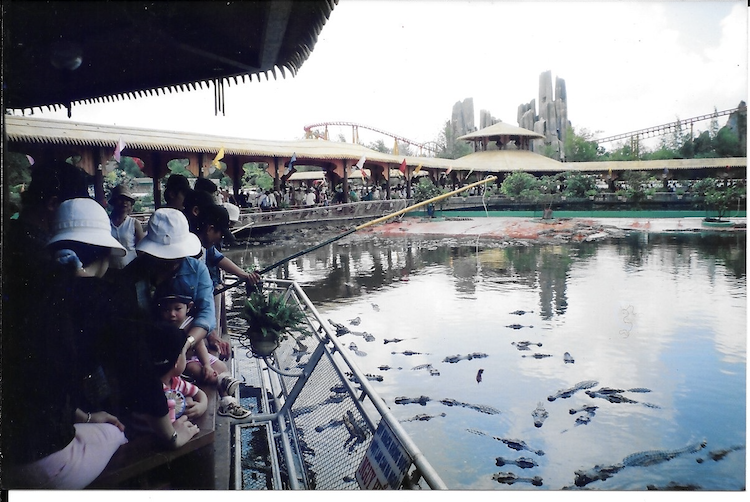

For example, at their “Kingdom of Crocodiles” attraction, I went “crocodile fishing”. For 15 cents I rented a bamboo pole with lump of raw meat tied to a string at one end of it and dangled it over a group of hungry crocs, mouths wide open in anticipation. They snapped. I pulled it away. They snapped again. I pulled it away again – until inevitably they won “the game” and ate. Thankfully, not my fingers and hands as well.

Crocodile fishing at Suoi Tien In Western terms, “Crocodile fishing” may not be politically correct – but based on the excited crowd I saw, it’s certainly spot on in Vietnam. Hong Kong Disneyland might not have an attraction like this one – but they could certainly learn from a park like Suoi Tien on how to bond with its target.

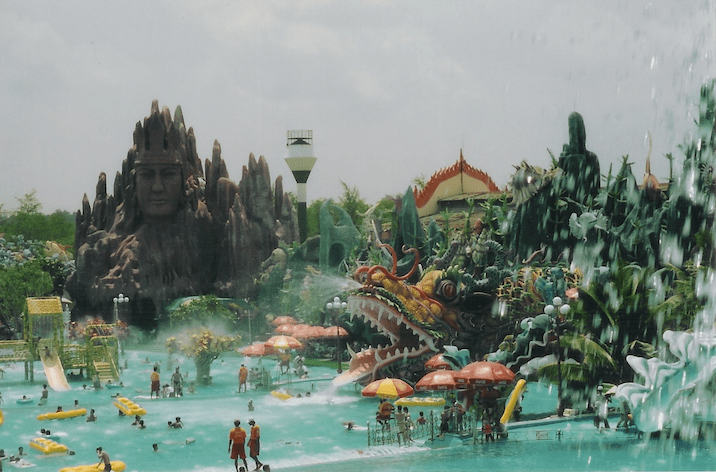

Crocodile fishing At nearly the same size as Hong Kong Disneyland, Suoi Tien’s appeal lies in offering attractions that are culturally unique to Vietnam. Like the massive public swimming pool called Tien Dong Beach. Surrounding it are mythical hills and palaces, a massive mist-spewing dragon and dominating the pool, park, and flat surrounding countryside a mountainous likeness of King Lac Long Quan, the mythological founder, with his wife Au Co, of the Vietnamese people. Yet this indigenous version of Mount Rushmore is a kind of Matterhorn ride – I hopped on a yellow raft and slipped and slided through the emperor’s head until I emerged wet and happy from a giant fish’s mouth.

But my Vietnamese history and cultural lesson didn’t end there. There is a giant statue of the Trung sisters, riding elephants on their way to defeat the Chinese in the 1st century. There is the Phoenix Palace where I visited the 12 levels of hell, a local version of Pirates of the Caribbean – after the pirates had passed to the “other side”. I descended into a dungeon where I saw some neat tortures: somebody getting sawed in half and put back together again; another being eaten alive by a hairy monster; a body squeezed into a large wooden basin and pummeled like a bunch of grapes being turned into wine.

Then I tried the Palace of Heaven nearby. The re-creation of an emperor’s court had it all: a stern emperor and court officials; beautiful ladies-in-waiting and in one tableaux, mannequins dressed as ghost princesses, swinging angelically from wires.

The adventures all have a Vietnamese theme that is relevant to its target as, say, the “The Haunted Mansion” or “Space Mountain” rides are to the visitors of Disneyland.

At Suoi Tien there was a more participatory attraction where I went down a small dingy elevator and “attacked” the “Citadel” in the ancient capital of Hue through a hidden fortress tunnel. “Defenders” of the palace “slapped” my legs as I passed deeper into the fortress.

There were also prosaic attractions like a rollercoaster, ferris wheel, paddle-boating, aquarium, small zoo and bonsai “forest”.

And less prosaic ones like the tent with the “freaks” exhibit. Some of the wonders preserved in alcohol were Siamese pigs; a two-headed calf; a calf with six legs; a chicken with a very, very long neck.

Everywhere there were crowds and long lines – and lots of happy faces. Like Hong Kong Disneyland, Suoi Tien is a big favorite of out-of-towners, coming to Saigon for a visit. Near the end of my visit I came upon the Heavenly Palace. I’ve never been a big fan of “dressing up” in costumes and having my photo taken. But in this Hue meets Las Vegas meets Anaheim attraction I couldn’t resist. So, for a few minutes I wore the headgear and robes of a Vietnamese emperor and had my photo taken on a mock-up of a throne.

While I certainly didn’t feel like a king, I took away from my day at Suoi Tien rich and culturally unique memories. Not repackaged ones sent from distant shores. Now Hong Kong Disneyland could certainly learn from that.

Published in South China Morning Post, September 13, 2006

-

Ju Ming Museum: A Sculptural Oasis in Taiwan

In 1542, sailors on a Portuguese ship heading to Japan spotted Taiwan and named it Ilha Formosa, beautiful island. While driving along the coastal road from Taipei to the Ju Ming Museum it’s easy to understand how the sailors arrived at that name. The coastline, studded with rock formations, is at once dramatic and forbidding. It may have also served as inspiration for Ju Ming, Taiwan’s greatest living sculptor.

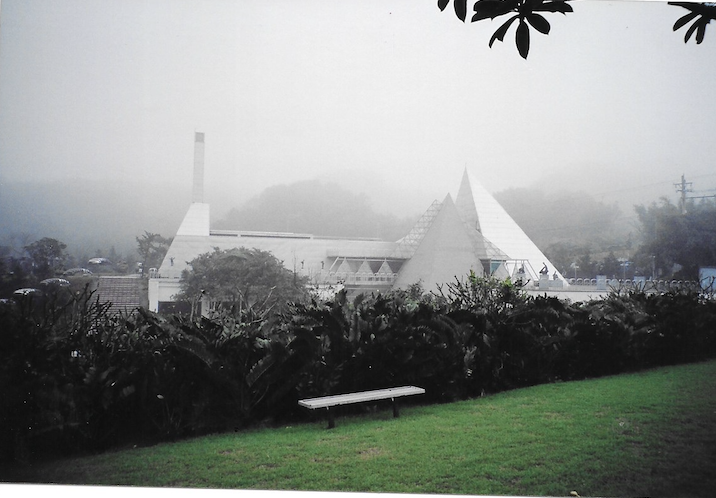

Ju Ming Museum building His museum, opened in 1999, was designed by him to showcase his vision in bronze, stone, clay and wood. While the focus on primarily one artist’s work is unique in Asia, in a nod to inclusiveness great artists from the both East and West are also exhibited. Taiwanese painters such as Chang Wan-chuan, Lee Cher-fan, Liao Chi-chun as well as Western artists such as Henry Moore, Andy Warhol, Joan Miro, Picasso, Bernard Buffet and Robert Rauschenberg can be seen there. The closest to a Western equivalent to it would be the Rodin Museum in Paris or the Picasso Museum in Barcelona – but minus the ego.

Born in 1938, Ju Ming began sculpting as an apprentice at the age of 15. For the next two decades he modestly viewed himself as just a talented craftsman and sought teachers such as the sculptor Yang Ying-feng to mould and shape his skill into true artistry.

Monumental Sculpture by Ju Ming In 1976, Ju Ming’s work, including his iconic Taichi Series, was featured at Taiwan’s National Museum of History. His Living World Series furthered his reputation internationally. In 1994 his work was featured at the Hakone Open-Air Museum in Japan, the first exhibition by a Chinese artist there.

Colorful sculptures inside the museum building I entered the 11-hectare museum through a white angular building, descending some stairs before walking down a long, white hallway. I had the impression that the architect’s vision was that the hallway was like a birth canal and the outdoor exhibition just beyond the glass doors a new way to see the world.

Sculpture with an urban theme I visited on a foggy weekday. Mist rolled over the works, at once obscuring and revealing them. Lack of sunlight dulled the color of the grass and the grey milkwood trees, but gave the works more gravitas as the Tai Chi figures were pushing at each other and the intrusive sky. The ever changing motion from the ground cover clouds helped to convey the stillness and movement of the figures, the uncanny sense that they were observers as well as the observed, like actors in a tableaux. While the figures were abstract or semi-abstract, the strength of their inner spirit was apparent. I was dwarfed by the size of the largest of the pieces, which at 15.2 meters wide by 6.2 meters high was the size of a small house.

Celebrating the Navy There was a series of pieces on the Taiwan military. A platoon of life-size sculptures of soldiers was marching, exhausted, on a path. In another piece, soldiers stood at attention while an officer addressed them. There was an eight-story high bare metal frame of a naval ship, its mast lost in the fog of that day, while Ju Ming’s sculptured sailors were ready to be reviewed. His parachutists descended towards a landing zone beneath a bridge that connected the two sides of the museum grounds. Pilots stood impassive beside a mock-up of a fighter jet. His military were less enshrined heroes than people worn down by duty and obligation.

Whether it’s the Tai Chi masters or the Taiwan military, Ju Ming’s inspiration comes from the land of his birth. His angular Tai Chi masters look as if they emerged from the rocky shores the Portuguese sailors saw centuries before.

His stature, and statues, are helping Taiwan to carve a separate cultural identity, at once a part of and yet distinct from China. On both sides of the Taiwan Strait he is viewed as a great Chinese artist. A visit to his museum will show you why.

Screenshot Published in South China Morning Post, April 18, 2007

-

Iconic Buildings Live Up to Hype as Billboards

SINGAPORE: There was symmetry to the moment: I was standing on the balcony of Singapore’s colonial-era iconic building, the Supreme Court, while taking a photo of its 21st century one: the Marina Bay Sands. The meanings of the two buildings couldn’t be more different yet more appropriate for their respective eras. The Supreme Court stood for rule of law in an unruly part of the world in the 1930s. And the triple-towered Marina Bay Sands, designed by Moshe Safdie, with its colossal boat-shaped SkyPark, stands for fun in a country that recognizes the economic value of “the pursuit of happiness.” As “billboards” advertising their respective messages, they work. The Marina Bay Sands, for example, just brought in a record-breaking profit of $314 million for its corporate parent, Las Vegas Sands.

Iconic buildings have been central to humanity since Stonehenge. Architecture has always been about context. This is what Moshe Safdie calls on his website, “Responding to the Essence of Place”. And also content, or “Shaping the Public Realm”, also from his website. Their purpose in ancient times was either to foster religion or generate fear and respect for the governing body. Whether it was the Parthenon on the Acropolis or the pyramids of Egypt, rulers created iconic buildings to secure their hold on the populace.

But now it is different. Culture and business, today’s soft power drivers, are the reason these buildings are created. Government involvement is more backseat: from encouraging the development through zoning laws, approvals or tax and other incentives.

It is perhaps Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao that started the latest wave of iconic buildings as billboards. Although Asia and the Middle East were already approving plans and laying foundations for their own monumental billboards before the Guggenheim was opened in 1997.

The Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, opened in 1998, signaled the emergence of Malaysia as more than a country of rubber and palm oil plantations. Architect Cesar Antonio Pelli said, “I tried to express what I thought were the essences of Malaysia, its richness in culture and extraordinary vision for the future.” And Taipei 101, from 2003 until this year the world’s tallest building, reminded people that Taiwan still mattered as a business hub and wasn’t overshadowed – yet— by China.

Iconic buildings can create a buzz that translates to perceptual and economic benefits over time. When the Burj-al-Arab opened in 1999, it put Dubai on the map as the ultimate luxury destination. Like the Marina Bay Sands, it communicated fun in a part of the world that is usually more associated with oil and the occasional war. The term “seven star” hotel was invented to describe the hotel. Looking like a colossal chrysalis from which a butterfly is about to emerge it has attracted celebrity guests and incalculable positive PR.

Dubai followed up this year with the can’t top this Burj-al-Khaifa. As Christopher Davidson, a University of Durham professor said, “The tower was conceived as a monument to Dubai’s place on the international stage.” The world’s tallest building by far it is a litany of superlatives: 828 meters high, 160 floors, world’s fastest elevators at 64 kilometers per hour, 12,000 workers and contractors involved in the building of it. When compared to the rest of the Dubai skyline it looks like it is nearly double the height of the next highest building. It is truly a Great Pyramid of Giza for our time. But its opening earlier this year was colored by the collapse of Dubai’s economy. Still, I believe that over time it will deliver on its promise to transform the city’s image. Scenes from Tom Cruise’s next “Mission Impossible” movie will feature the building, creating buzz for Dubai that it needs in its economic recovery stage.

Not that Qatar will allow its sister gulf state to grab all the attention easily. Doha, the capital of Qatar, now has its own iconic building: the Museum of Islamic Art, which opened in 2008. The I.M. Pei designed building showcases a stunning collection of Islamic Art to remind the international community of the richness — not just riches – of the Arab world. Like the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao, it’s a transformative culturally-oriented building, making Doha a destination in its own right. Perched pyramid-like on the edge of Doha Bay, it is a visual anchor of the city. As the Qatar Museums Authority website says: “It will bring the world to Doha, but it will also connect Doha to the world.”

And of course China is building a number of iconic buildings to flesh out its progressive 21st century image. I remember standing on the Oriental Pearl building in Shanghai, that 1990s Flash Gordon inspired image of the future with its spheres and pointy spire and looking down on the iconic buildings of the 1920s on the Bund with their colonial-era stolidness, projecting wealth and power with fluted columns and granite. And I looked up at the iconic building of the 21st building, the Shanghai World Financial Center building, opened in 2008, which at one angle looks like a giant bottle opener overshadowing the nearby Jin Miao tower. Shanghai, like the New York it seeks to emulate, and Hong Kong, which it is overtaking, is a city of iconic buildings.

When will this latest wave of building competition end? Not anytime soon. If you want to understand the power of iconic buildings to attract attention to a city trying to compete in this globalized economy, then think of the cities that don’t have them. Bangkok perhaps. Or Mumbai. Or Jakarta. Or Manila. You’ll discover that the negative clichés about these metropolises tend to define them. In a world where a positive image translates to economic advantage, iconic buildings give just that more of a winning edge. You only need to take another look at the Marina Bay Sands and its recent profits to see that the gamble to build it has paid off. As British archaeologist, Jacquetta Hawkes, said, “every generation gets the Stonehenge it deserves – and desires.”

Published in The Straits Times, November 2, 2010

-

Miri: Seahorse City on the South China Sea

If you’re in Miri, chances are you’re on the way to somewhere else. The second largest city in the Malaysian state of Sarawak, Miri is a crossroads and stopover destination. In my case we were heading to Mulu National Park from Singapore and needed to overnight there. But it’s also a good stopover if you’re driving from Kuching to Brunei. Miri is also popular with expats from Brunei who visit beachside hotels like the 5 star Marriott for the weekend with their families and a chance to drink some alcohol, which is not allowed back in Brunei.

Niah Caves for Rock Paintings or Bird’s Nest

But Miri is worth more than just an overnight or weekend stay. The Niah Caves are about an hour drive from the city. Human remains some 40,000 years old have been found there. It’s the oldest settlement in East Malaysia and Painted Cave has rock paintings over 1,200 years old. Bird’s Nest, that seriously expensive Chinese delicacy, is also harvested here from Swiftlet nests. So is bat guano. According to tradition, the local Penan tribe get to harvest the Bird’s Nest while the Iban the bat guano.

Lambir Hills National Park

Just 32 kilometres away is Lambir Hills National Park, a tropical rainforest with an astounding 237 different species of birds as well as wild pigs, gibbons, flying squirrels. There are great trails to get into the park’s terrain with its cooling waterfalls and bathing pools.

Birthplace of Malaysian Petroleum Industry

Miri is also where the Malaysian petroleum industry got its start, with the first well dug in 1910. The old derrick, called the Grand Old Lady, has been preserved. At its base are statues of Chinese labourers depicted as manually doing the drilling. Wrapped around it is a curving monument with panels describing the history of the industry in Miri. The sleek Petroleum museum just steps away is definitely pro-big oil and understandably so. The oil business built Miri and is its main income contributor. Opened in 2005 it goes in-depth into how the industry works, including a scale model of a drilling platform. When I visited there was an informative exhibit on the indigenous people in Sarawak. Outside the museum is a sweeping view of the city and the sea from its on the top of Canada Hill.

Ethnically Diverse

Of 27 ethnic groups in Sarawak, 19 are in Miri. Chinese is the largest followed by Iban, Malay and Melanau. The Miri Handicraft Centre showcases indigenous crafts including flutes, baskets, and kueh, a Malay dessert. It’s well a browse.

The San Ching Tian temple is the largest Taoist temple in Southeast Asia and well worth a look for its huge ceramic dragon.

Popular Dive Spot

Miri is popular dive spot with the Miri-Sibuti Coral Reefs National Park just off the coast at a depth of 7 to 30 metres. There are some wrecks that you can easily visit. It’s not as well known as other famous sites in Malaysian Borneo but you can quickly reach the park from Miri.

Why Seahorse City?

Why did I title the piece “Seahorse City”? Around the city are statues of seahorses: at a roundabout; a restaurant named Seahorse Bistro and a giant statue overlooking the sea. When I asked town’s people no one knew why the seahorse is such a commonly used symbol. But it is. So I thought, let’s call it Seahorse City. It has a nice ring to it. Especially for a nice stopover.

Published in Asian Journeys magazine, October-November 2015

-

Jakarta’s Money Central

A trip to Jakarta is usually a chore. Traffic can be so bad that you’ll spend more time commuting to a sight than you did at the sight itself. With a little digging, though, the city has some one-of-a-kind cultural gems.

In Kota, also known as Old Batavia, are a number of museums in stolid Dutch colonial buildings better suited for northern European winters than the tropics. The Fatahillah, Shadow Puppet, and Ceramic museums all sit around a picaresque cobblestoned square where you can almost forget the jammed traffic in the streets around you. Two of the most engaging museums though are nearby and next to each other: The Bank of Indonesia and the Bank Mandiri museums.

The Bank of Indonesia museum is the flashier of the two, with informative exhibits that underline its role as a pillar of a volatile ever-evolving society. After three years of meticulous restoration, it was opened July 2009.

MUSEUM WITHIN THE DE JAVASCHE BANK BUILDING

The museum sits within what was once the The De Javasche Bank. That bank, also known as the Bank of the East Indies, was founded in 1828 and moved into this building by Dutch architect Edward Cuypers, in 1909. As the colonial central bank it played a stabilizing role through the Japanese occupation, the 1945 declaration of independence until finally the Indonesia government nationalized the bank in 1953 and turned it into the Bank of Indonesia.

While the replacement of De Javascche Bank was a nationalist move, it is curious to note the original Bank of Indonesia logo was closely aligned with the De Javasche logo: the letter J was changed to the letter I without altering any other design elements. So much for continuity.

EARLY 20TH CENTURY DESIGN

For early 20th century design aficionados, the museum is a treat. The lobby has tiled azure pillars supporting a high vaulted ceiling. Through an archway is the old teller system. A bank customer would go into an enclosed room and do their transactions through a wire mesh.

The exhibits take you through Indonesia’s mercantile history. Life size mannequins of laborers loading sacks of spices for shipment to Europe for the VOC company; Dutch colonialists having dealings with pigtail wearing Chinese; even soldiers firing on the Japanese in a World War II scene. The message was clear: the bank and nation’s history are intertwined.

STACKS OF GOLD BULLION

And, of course, no visit to a central bank is complete without seeing its gold bullion. Within a clear plexiglass enclosure are stacks of gold bricks. And nearby, inside a spacious walk-in vault, are displays of Indonesian money from the 14th century to the present.

While I like history, the restored to its original grandeur building was worth lingering in: the bank’s boardroom with its malachite green-tiled walls and intricate stained glass windows, a grandfather clock in the rear; the huge open-air courtyard covered in decorative tiles and potted trees surrounded by the bank’s white-colored pillars and covered interior walkways. The building projects the stability it sought to achieve.

BANKING IN THE 1930S

While the Bank of Indonesia museum projects a stolid national institution, the Bank Mandiri museum next door is more lively, a sort of this is how banking really was in the 1930s. The building originally was the Netherlands Trading Society. Designed by Dutch architects JJ de Bruyn, A.P. Smits and C van de Linde in an art deco style it was opened in 1933. The building was nationalized in 1960 to become part of the Bank Export Import Indonesia until finally through a series of mergers it became Bank Mandiri in 1999.

The museum has a cluttered hodgepodge collection with teletypes from various eras, paper shredders, logbooks, securities, antiquated computers, old currency, and colonial era antiques.

ART DECO AT ITS BEST

Fans of art deco will be delighted. As you walk in the massive building you see a 50-meter long polished counter where a lot of the bank business was conducted with customers. Behind the counter bank officers sat at elegant wooden desks on polished red-tiled floors. You can stroll amidst the exhibits and mannequins to get more of the bank experience. The walk-in vault in the basement was the highlight. There were walls lined with safe deposit boxes, and a mannequin bank officer and his female assistant going through a log book while soldiers in wide-rimmed hats stood nearby.

PANORAMA VS. NOSTALGIC SNAPSHOT

While the Bank of Indonesia museum is structured and organized as a panorama walk through history, Bank Mandiri is a snapshot focused on a nostalgic 1930s experience. Two sides of Indonesia banking: one depicting the nation’s history; the other it mercantile spirit. Both set in stunning architectural examples of the early and mid-twentieth century. A visit to both will give you a perspective of Jakarta that will be refreshing after a long bumper to bumper drive.

Published in the April-May 2015 issue of Asian Journeys magazine